STRUGGLE FOR THE WORLD :: A BOOK :: by James Burnham ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Burnham ) ::

-

...

CONTENTS <Contents> Part 1. —The Problem

Part I. —The Problem (page in book )

1. The Immaturity of the United States (1)

2. Is It Really One World? 14

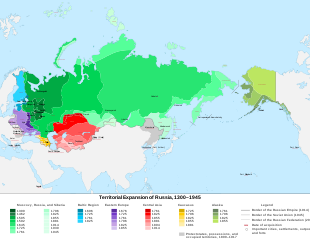

3. The Political Consequences of the Atomic Bomb 26

4. World Government or World Empire? 42

5. The Nature of Communism 56

6. From Internationalism to Multi-national Bolshevism 75

7. The Goal of Soviet Policy 90

8. The Weakness and Strength of the Soviet Union 114

9. Is a Communist World Empire Desirable? 122

10. The Main Line of World Politics 130

Part II. — What Ought to Be Done

11. The Renunciation of Power 136

Part III. — What Could Be Done

12. Political Aims and Social Facts 144

13. The Break with the Past 150

14. The Supreme Object of United States Policy: Defensive 161

15. The Supreme Object of United States Policy: Offensive 181

16. The Internal Implementation of Foreign Policy 200

17. World Empire and the Balance of Power 211

18. Is War Inevitable? 222

Part IV. — What Will Be Done

19. The Policy of Vacillation 231

20. The Outcome (242)

< The END > < end of the book >

COMMENT & REVIEWS

SOURCE: https://www.independent.org/publications/tir/article.asp?id=66 "James Burnham and the Struggle for the World" "... Daniel Kelly ISI Books, 2002 - Biography & Autobiography - 443 pages

... James Burnham (1905-1987) was one of the most influential anticommunist figures of the Cold War era, as Daniel Kelly's fascinating biography makes clear. But like many anticommunists, Burnham first started on the other side. Kelly tells the story of Burnham's political journey and intellectual transformation into -- as Richard Brookhiser once stated it -- "the first neoconservative." Including fascinating vignettes with characters as diverse as George Orwell, Arthur Koestler, Andre Malraux, and Ezra Pound, Kelly's lively and definitive narrative must be read not only by anyone interested in the life of this seminal conservative thinker and Cold War strategist, but by all those who want a better understanding of the forces behind the most important ideological clash of the modern age.

... From inside the book ..."

SOURCE: https://www.commentary.org/articles/maurice-goldbloom/the-struggle-for-the-world-by-james-burnham/ "... All in all, The Struggle for the World is a good enough book in part so that its failure to be better in toto becomes doubly exasperating. Perhaps this failure is due to the fact that Mr. Burnham still thinks in terms of a rigid theological orthodoxy—though this time neither Catholic nor Trotskyist—from whose premises the world may be deduced entire, and outside of whose fold there is no salvation. As to the last, he may be right. But if he is, then there simply is no salvation, at least for the Western Civilization in whose preservation Mr. Burnham is interested. ..."- SOURCE: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/capsule-review/1947-10-01/struggle-world "... Reviewed by Robert Gale Woolbert ( October 1947 )

The author of "The Managerial Revolution" postulates the inevitability of a conflict between the United States and a Soviet Union embarked on a calculated career of world conquest. He finds that objective conditions, in particular the atomic bomb, call for a universal state (he cites Toynbee) created under the aegis of a single Power, since the formation of a voluntary world government is presently impossible. He therefore urges the American people to prepare for the final showdown by going on a permanent war footing, with all that this involves in loss of personal, political and economic liberties. ..."

"The Managerial Revolution" "PDF" < Google

- https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.17923

- https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.17923/2015.17923.The-Managerial-Revolution_djvu.txt

- https://ia801603.us.archive.org/11/items/in.ernet.dli.2015.17923/2015.17923.The-Managerial-Revolution.pdf

"THE STRUGGLE FOR THE WORLD" (A BOOK) by James Burnham ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Burnham )

Part I THE PROBLEM < go to Contents>

1. The Immaturity of the United States THE THIRD WORLD WAR began in April, 1944. <fiction The details of an incident that then took place have not been disclosed. "Manchuria" > https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manchuria The incident itself, even less dramatic than the dropping of a small bomb on a "Manchurian bridge", was hardly noticed behind the smoke of clashing armies and the rubble of cities falling. The few ships of the remnant of the Greek Navy, operating as a unit under the British Mediterranean Command, were in harbor at Alexandria. [ Google MAPs Coordinates: 31°11′51″N 29°53′33″E ] The Greek sailors, joined by some Greek soldiers stationed near by, mutinied. It was not a serious revolt, in either numbers or spirit. A few shots were fired, a few lives lost. The British rounded up the mutineers and placed them, for a while, in concentration camps. A few leaders were punished; but soon - the trouble was patched up and forgotten. It was recalled briefly by some when, later, a short, bitter civil war broke out in Greece proper. We do not know the details of what happened in the mutiny; but the details, important as they may be for future scholars, are unnecessary. We know enough to discover the "political meaning" of what happened, and for this details are sometimes an obstacle. The mutiny was led by members of an organization called ELAS. ELAS was the military arm of a Greek political grouping called EAM. EAM was a seemingly heterogeneous alliance of various Greeks with various political and social views. But EAM was [in fact] directed by the Greek Communist Party. The Greek Communist Party, like all communist parties, is a section of the international communist movement. International communism is led, in all of its activities, from its supreme headquarters within the Soviet Union.

[ communism > https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Communism ] "... Dissolution of the Soviet Union ( Further information: Dissolution of the Soviet Union )

With the fall of the Warsaw Pact after the Revolutions of 1989, which led to the fall of most of the former Eastern Bloc, the Soviet Union was dissolved on 26 December 1991.

It was a result of the declaration number 142-Н of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union.[108] The declaration acknowledged the independence of the former Soviet republics and created the Commonwealth of Independent States, although five of the signatories ratified it much later or did not do it at all. On the previous day, Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev (the eighth and final leader of the Soviet Union) resigned, declared his office extinct, and handed over its powers, including control of the Cheget, to Russian president Boris Yeltsin. That evening at 7:32, the Soviet flag was lowered from the Kremlin for the last time and replaced with the pre-revolutionary Russian flag. Previously from August to December 1991, all the individual republics, including Russia itself, had seceded from the union. The week before the union's formal dissolution, eleven republics signed the Alma-Ata Protocol, formally establishing the Commonwealth of Independent States, and declaring that the Soviet Union had ceased to exist.[109][110]

Post-Soviet communism ...

The Vietnamese Communist Party's poster in Hanoi

As of 2022, states controlled by Marxist–Leninist parties under a single-party system include: the People's Republic of China, the Republic of Cuba, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.[nb 4] Communist parties, or their descendant parties, remain politically important in several other countries.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the Fall of Communism, there was a split between those hardline Communists, sometimes referred to in the media as neo-Stalinists, who remained committed to orthodox Marxism–Leninism, and those, such as The Left in Germany, who work within the liberal-democratic process for a democratic road to socialism,[116] while other ruling Communist parties became closer to democratic socialist and social-democratic parties.[117]

Outside Communist states, reformed Communist parties have led or been part of left-leaning government or regional coalitions, including in the former Eastern Bloc. In Nepal, Communists (CPN UML and Nepal Communist Party) were part of the 1st Nepalese Constituent Assembly, which abolished the monarchy in 2008 and turned the country into a federal liberal-democratic republic, and have democratically shared power with other communists, Marxist–Leninists, and Maoists (CPN Maoist), social democrats (Nepali Congress), and others as part of their People's Multiparty Democracy.[118][119]

China has reassessed many aspects of the Maoist legacy, and along with Laos, Vietnam, and to a lesser degree Cuba, has decentralized state control of the economy in order to stimulate growth. These reforms are described by scholars as progress, and by some left-wing critics as a regression to capitalism, or as state capitalism, but the ruling parties describe it as a necessary adjustment to existing realities in the post-Soviet world in order to maximize industrial productive capacity.[citation needed] In these countries, the land is a universal public monopoly administered by the state, and so are natural resources and vital industries and services.

The public sector is the dominant sector in these economies and the state plays a central role in coordinating economic development.[citation needed] Chinese economic reforms were started in 1978 under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, and since then China has managed to bring down the poverty rate from 53% in the Mao era to just 6% in 2001.[120] ..."

Vladimir "Putin" has embraced "Democracy" < Google > ...results ...

Politically understood, therefore, the Greek mutiny of April, 1944, and the subsequent Greek Civil War, were "armed skirmishes" between, the Soviet Union, representing international communism, and the British Empire. In the Second World War, however, which had still - at that time - more than a year to run, Britain and the Soviet Union were allies against a common enemy. We have been recording, we thus see, another war. In the late summer of 1945, Japan fell. The Red Army, though somewhat tardy in arrival, took quick control over Manchuria (as defined above) and parts of North China. During the time that followed, the communist armies of what had been called the "Yenan Government" ( 1, 2, 3 ... ), sheltered, equipped and in part "officered" by the Red Army [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Red_Army ] , attempted to establish independent sovereignty in Manchuria (as defined above - and below), northern and some of central China. [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soviet_invasion_of_Manchuria ] These armies met in battle with the armies of the Chungking Government [link] , trained and equipped with the help of the United States Army, and transported toward the scene of action by ships of the United States Navy. But in the Second World War, the United States and the Soviet Union were allies. In the Spring of 1946, a little late by the diplomatic clock, the Red Army (defined in fiction & reality - above) withdrew from northern Iran .

[ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran ] hh ( map)

As is the custom of occupying armies, it [ the Red Army ] left behind among the population a reminder of its stay.

The young offspring was, however, more formidable than usual:

a new little red army, trained, equipped and led by the aid of its political father,

with a new autonomous state and a new political party for its playthings.

This "new little army" faced south and southwest and southeast, toward India, toward the Persian Gulf,

toward the great oil fields of the United States and the British Empire, flanking the land bridge to Africa.

We are inured to the fact that a "great war" stirs so deeply the "social cauldron" [that]

the fumes and bubbling cannot be expected to subside at the mere official declaration of the end of hostilities.

Subsidiary wars, mass strikes, civil wars, colonial revolts are the accompaniment of the last stages of great wars,

and the usual aftermath. [ In 1947 - they did not have the International Crimminal Court - but, they did have Nuremberg. ]

This was true of the First World War, in the period from 1917 to approximately 1924,

and it is true now of the postlude to the Second World War.

The civil wars and strikes and revolts are a phase of the war.

More accurately, both they and the war are phases of a wider historical process

- which comes to an acute head in the outbreak of large-scale fighting.

VE day May 8 , 1945

> https://www.defense.gov/Multimedia/Experience/VE-Day/

VJ day August 15, 1945

> https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/v-j-day

* The Russian Revolution, the civil wars in Germany in the years

1918-24, the uprisings in India, the Allied intervention in revolutionary Russia,

the Balkan revolts, the Turco-Greek war, the strike waves in nearly every country, were all part of what may properly

be called the First World War. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Causes_of_World_War_I < Causes of World War I

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Causes_of_World_War_II < Causes of World War II

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pan-Slavism "Pan-Slavism" & "Putin" > https://imrussia.org/en/nation/527-the-birth-of-pan-slavism

* (these events) Not until their conclusion was the war itself brought to an end. World political conditions quieted — relatively — down. The interim period of recuperation set in, and lasted until the preparatory stage of the new war began. [ World War III ]

We now realize that the first battles of the Second World War were fought in Spain, and in China from 1937 on.

The new war (WW2) reached its overt military climax from 1940 to 1945 (the battles of 1939 were still pre- liminary), and is now fading out, with the expected aftermath. [ Mussolini > https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benito_Mussolini ] The strike waves in the United States, the end of the Third Republic in France [ link], the ousting of the Italian monarchy [link], the Labour Party victory in England [link], the colonial disturbances in the Far East (below), all these may be included as part of the Second World War.

SOURCE: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1946/12/the-far-east/656564/ ( https://cdn.theatlantic.com/media/archives/1946/12/178-6/132381470.pdf )

"... The Far East -- DECEMBER 1946 ISSUE ... IT TOOK from three to five years for the results of the First World War to develop a full head of political pressure in Asia. It is therefore not surprising that only now, a year and a half after V-J Day, is it becoming possible to measure political events and trends in Asia after the Second World War with sufficient accuracy to make meaningful comparisons with the post-war Asia of twenty or twenty-five years ago. ... Already two great changes stand out. Russia, which for some years after the First World War was a wavering question mark, has become a solid exclamation point. And in the field of Asiatic nationalism, there has been a major shift from the plane of theory to the plane of action. ... A quarter of a century ago, a man like Sun Yat-sen [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sun_Yat-sen ] could see clearly, in theory, what he wanted - but methods were still experimental. The personnel of nationalist revolution was top-heavy with generals and colonels and fatally weak in steady, dependable sergeants.

Today, nationalism is a going concern. Both its conservatives and its leftists know how to tap and organize political manpower by deliberate selection along lines of social and economic interest.

These two great changes must be analyzed in combination. A quarter of a century ago the great powers had not yet conceded the ability of the Bolsheviks to survive even in Russia.

The powers which invaded Russia and backed the Kolchaks and the Denikins were also the major colonial powers.

The Russians, in their struggle for survival, therefore shouted the most bloodcurdling slogans they could think up, in order to incite the colonial peoples and create a diversion in the rear of the governments which were trying to stop the Revolution.

In the colonial countries, however, and among the colonial peoples, Russian policy had no real roots. Even the most radical colonial leaders who began to call themselves "Communists" were not Russian trained. They were intellectuals, few in number, who had been in contact with Western European radical thought, and they were labor leaders, even fewer in number, who had learned something of the technique of trade-union organization. The

Russians could in fact do very little in the way of creating colonial unrest; all that they could do was to take advantage of colonial unrest already existing.

The shift in combination can thus be well expressed by pointing out that now it is the colonial nationalists and revolutionaries who are in a position to take advantage of the fact that Russia exists.

Russia — and not just Russia, but the "Soviet Union", under Communist leadership and with a socialized economy — is a solid fact.

Asia’s leadership

Leftist leaders - in Asia - now believe that they can speed up the emancipation of their own peoples either under conditions of world hostility toward Russia or under conditions of world coöperation.

If coöperation is to be the policy, they can take part in the general coöperation. If hostility is to be the policy, then they can put pressure from the rear on any country that has turned its face in hostility against Russia.

Moderate leaders believe that the balance of world power - between Russia and the Anglo-American bloc - leaves them room for maneuver. They have long abandoned the Gandhi dream of a return to an idyllic, unmechanized, pre-Western — and unreal — Asiatic past. They are convinced that, however much they dislike their rulers, they must borrow techniques of political organization and economic production from these rulers if they are to survive in the modern world.

Many of them believe that they can also borrow from the Soviet Union short-cut methods of education, political mobilization, and speeded-up economic progress without being captured themselves by Communism, or even Socialism. They can maintain freedom of choice, however, only as long as the balance between the Russians and the capitalist countries remains a balance.

The moderate leaders therefore - resist Russian infiltration and excessive leftward trends within their own countries; but they also resist pressure from the outside to make them climb on any anti-Russian bandwagon.

They feel safer with a capitalist world to hold Russia in check; but they also feel safer with a Russia strong enough to prevent capitalism from reverting to wide-open imperialism.

For the moment, however, it is the rightists of Asia who are most active; and they, too, take advantage of the existence of Russia. Last thing at night, the rightists of Japan remind General MacArthur to look under the bed for subversive trade-unions.

They have maneuvered Mr. George Atcheson, MacArthur’s political spokesman, into the weird position of defending not only the state of affairs in Japan but Japanese aims as “virtually identical with the Allied aims.” Allied aims are presented and defended as aims which allow the Russians no elbowroom. Since the anti-Russian Japanese are also the Japanese who financed and abetted the Japanese militarists from the Mukden Incident to Pearl Harbor, the effect of such special pleading is to make Mr. Atcheson the best spokesman of the Japanese militarist point of view since the ineffable Matsuoka.

The Philippine revolt spreads

In the Philippines, the drive of the rightists is to get American equipment and aid for the suppression of agrarian unrest.

Although an old directive from President Truman, now forgotten, urged considerate treatment for the agrarian guerrillas, on account of their considerable services against the Japanese, the present drive for law and order defers the satisfaction of even legitimate grievances, and gives priority to the suppression of those who have grievances.

Thus far, the result has not been a narrowing of the area of revolt, but a spread of revolt to new areas. Several thousand former guerrillas have seized plantations which once belonged to the prosperous Japanese colonists in Mindanao, and are now squatting on them.

Title to these plantations had been transferred by the United States Alien Property Custodian, for one dollar, to the Philippine government.

The conflict with the squatters has thus become a direct conflict between the people of the Philippines and their government.

President Roxas has made some statements, which read excellently, on the subject of distribution of farm lands, but the trouble lies in an old and deeply intrenched technique of political abuse. New farm lands cannot be opened up without new roads; when new roads are to be built, knowledge of them is leaked to those who are politically on the inside, and the adjacent land is taken up by landlords before claims can be filed by bona fide homesteaders.

Since the most powerful supporters of President Roxas regard this kind of graft as a legitimate perquisite, the only way in which he could restrain them would be to increase the political rights and representation of the peasants, who are his only strong, organized opposition; and since this is exactly what he is not prepared to do, the war of internal conquest against the peasants goes on.

The Korean experiment

In Korea, the rightists also jumped into the lead at the beginning of the American occupation; but because the Korean rightists, in addition to having almost no popular support, are unbelievably incompetent, the increasingly agonizing headache of the American occupation problem threatens to outweigh the satisfaction of blocking the Russians. The word has already been spread in Washington to lay off expressions of admiration and support for Syngman Rhee, because the Military Government is now ruefully convinced that the more he is supported, the more unpopular the Americans become.

Disturbances in Southern Korea are becoming more and more widespread. Responsibility for disorder is attributed to “inspiration” from across the border in Russian-occupied Northern Korea. The rare Americans who get into the Russian zone report that the Russians are also unpopular, and that Koreans there will take the risk of sidling up to Americans to whisper, “Russians bad; Americans good.” But for some reason, in the dismal competition to see which of the two occupying forces can make itself the more thoroughly disliked, the Russians have not had to face the kind of widespread, open, and popular manifestations of resentment which harass the Americans.

This may be because the Americans do not organize “inspiration” in the southern zone for infiltration into the northern zone. Or it may be because the Russian occupation forces are much larger, and able to crack down on popular resistance before it gets organized. Or it may be that the Russians are more intensely disliked, but by small groups of people, such as the landlords, while the Americans are more vaguely disliked, but by larger groups, such as the peasants. At any rate the situation cannot be cleared up until it is thoroughly aired; and Americans returning from Korea are outspoken in saying that it is high time for an airing.

Chinese puzzle

It is in China, however, that all issues linked with the position of Russia, the influence of Russia, and even the mere idea of Russia lead up to the biggest crisis. And this crisis tends more and more to become a crisis in American politics.

Already the gloves are off. Criticism of the extent of American intervention in China will increasingly be counterattacked as appeasement of Communism and of Russia. Demand for all-out support of the Kuomintang as the “only legitimate and recognized” government in China will increasingly be identified with a policy of hostility to Russia on all issues and in all countries, throughout the world.

The first subject of debate is General Marshall’s mission. Has General Marshall failed? It is noteworthy that those who were the first to say that General Marshall had been sent on an “impossible” mission, and the first to advise that he be withdrawn, are those who demand, on all issues, a policy of hostility to Russia. On the other hand, the Chinese Communists have been increasingly reckless in accusing General Marshall of condoning aid to the Kuomintang to an extent that invalidates his function as an impartial mediator.

The truth is that General Marshall’s mission has neither failed nor succeeded. It has merely been tacitly suspended. The real issue is not the monthto-month aid we are giving to the Kuomintang. That aid has been far too little to constitute a decisive intervention. It has in fact merely kept the Kuomintang from collapse and made possible the prolongation of a military stalemate which is still evenly balanced, in spite of the loss of Kalgan by the Communists.

To say this, is the same thing as saying that the real issue is whether to grant an enormous increase in aid to the Kuomintang, in order to enable it to assert a clear military superiority over the Communists, or to decrease American aid very slightly, which would instantly force the Kuomintang to make concessions to popular demands for a coalition government. It is because this fundamental decision has not been taken that General Marshall’s mission can be regarded as in suspension; and it is a fair inference that policy in China has been under review at the White House level.

The importance of the loss of Kalgan or Chefoo by the Communists should not be exaggerated. The “prestige” troops of the Kuomintang, its American trained and American-equipped divisions, were fought to a standstill in the mountains between Peiping and Kalgan, suffering heavy attrition, which meant the acquisition of a lot of American equipment by the Communists. Kalgan was entered by the troops of Fu Tso-yi, a semi-independent war lord. Thus while the Kuomintang “won,” it won without prestige for its crack troops, and in a way which encourages independent warlordism.

Moreover the Communists, while losing Kalgan, swung around and tore up a big stretch of the strategically important Peiping-Hankow railway. By disrupting Kuomintang communications more effectively than they had ever disrupted Japanese communications, they demonstrated once more that the Kuomintang is not so formidable an enemy as the Japanese were. The military situation, in fact, is still a stalemate.

Conscription, inflation, poverty

A military stalemate can last indefinitely, but there is no such thing as a political and economic stalemate. In politics and economics, a situation either gets better or it gets worse. In China, the situation is getting worse for the Kuomintang. When Kalgan was “liberated” from the Communists, no less than a quarter of the population, instead of waiting to greet the liberators, fled into the mountains. Of those who remained, Benjamin Welles cabled to the New York Times that “it was obvious that the Chinese civilans who were drawn up along the main streets to cheer the arrival of the Nationalist officials were not moved by any overwhelming emotion.”

Hesitation in welcoming Kuomintang liberators is explained by the fact that the Kuomintang, for lack of popular support, is being forced to increasingly harsh measures. Heavy losses in the field have led to the resumption of conscription with full wartime rigor, in a war-weary country.

Two new measures are especially ominous. Communist currency is being repudiated, instead of exchanged, in areas recovered from the Communists. As a result, inflation and poverty are flooding regions which, under the Communists, had been prosperous and had been secure against inflation. Even more drastic is the cancellation of Communist land reforms — a cancellation which all too often penalizes the peasant, who fought against the Japanese, in favor of the landlord, who either ran away or collaborated with the Japanese.

Such measures bear most harshly on all nonCommunists who prospered while the Communists were around. Worst of all, they make it nakedly clear that all the Kuomintang’s financial and material aid from America is being used for civil war, and none of it for much-needed reform. ... "

<end>

But the events that I have begun by citing — the Greek mutiny and civil war, the Chinese civil war, the Iranian conflict — are of a different character.

They are not part of the Second World War, nor of its accompaniment nor aftermath. The forces basically opposed in them — opposed and clashing by arms, as well as by economic and diplomatic competition — are not aligned as were the opposing forces of the Second World War.

One of the main power groupings of the war has, indeed, been eliminated altogether.

Moreover, the new conflict [WW 3] pushes through those other disturbances which might, from one point of view, be judged as part of the war's after- math.

The comforting opinion [that] the world troubles - since August, 1945, are in a way "normal", the natural features of a time of settling- down and readjustment, like the headache and queasiness following a heavy drunk, is a delusion.

These troubles are not a hangover, but the first sips in a new bout. ( The armed skirmishes of a new war have started before the old war is finished. )

A "general peace agreement" is impossible - not because leftovers from the old war are still unswept, but - because the debris of a new war is already piling up.

After these years of so much death and suffering and exile and destruction, there is a great weariness in the world, and a hope for rest.

It is hard to say, and still harder to believe, that this hope is empty, that there will be no rest, that a new war has already begun.

Nevertheless, this is the truth, and the penalty for denying this truth will be heavy.

Preliminary skirmishes, of course, even bloody skirmishes, are not identical with the grand battle.

Sometimes, even after the skirmishes have been fought, with dead on both sides, the battle itself is delayed, or, for the time being, avoided.

Sometimes, perhaps, the battle never does take place, though only if the issues at stake are resolved by some other means.

We can, then, consider it at least possible that the Third World War may never expand much beyond these preliminary stages, might end its life in its beginning,

like a new bud late-frosted. But what chance to avoid or to win the battle would a commander have who refused to believe the reports of his scouts, who would not listen when told that shots had already been exchanged, and who lolled carelessly in his tent, playing cribbage with his aide, and arguing the tactical merits of yesterday's engagement?

The United States has made the irreversible jump into world affairs. ( The Truman Doctrine > https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Truman_Doctrine )

It [ the United States ] is committed everywhere, on every continent, in every major field of social action, and it can never again withdraw.

In the Third World War, the United States, whatever the wishes of its citizens, is one of the two dominating contestants.

But socially, politically and culturally, the United States is not prepared for the "world role" which it is nevertheless compelled to play.

Faced with the tasks of full social maturity, the United States is itself mature in one field alone: in the development of the technique of production.

MASS PRODUCTION

In this, Americans themselves often do not understand their unparalleled supremacy. There is not, and has never been, anything approaching American methods of production. The last war showed that it is almost impossible to set goals too high for American factories to reach. Whether hairpins or battleships, air- planes or carpet slippers, cement or the most delicate precision in- struments, machine tools or penicillin, the United States can, so far as technique goes, flood the earth with them.

It is not so much in the machines themselves, where England and Germany and perhaps Sweden and Switzerland have done better, that the specific United States superiority lies. It is rather in a talent, by now almost a national characteristic, for the large scale organization of production.

England and Germany could build finer ships and airplanes and cameras, but they could not organize the hundreds of thousands of men and machines and secondary supplies and plants and freight cars and trucks into functioning organisms out of which could issue the immense quantities of very good, if not the finest, ships and airplanes and cameras.

This abiLIty - to organize production - is so well established that it seems capable of being applied at will, or under pressure, to new and unprecedented problems.

There is an instructive contrast between the petty Nazi attempts to manufacture atomic bombs, and the colossal, integrated Manhattan Project. Almost none of the fundamental research was done by Americans. The true creative energy of the United States was expressed in the organization and its mass functioning. The achievement was the same with blood plasma, radar, new drugs, or K rations.

The same talent was notable even in the military conduct of the war. The War and Navy Departments, the generals and admirals, inferior in the niceties of military tradition and science to those of other nations, were heroic as mass organizers. They hurled at the enemy overwhelming quantities of supplies, men, shells, food, ships, trucks, tanks, planes, so that the mistakes and crudities of details were buried in the mass.

The military methods were in accord with the American genius. To send thousands of planes and two million tons of shipping against a small Pacific atoll would have been absurd for any other nation, but it was exactly American.

From this supremacy in the technique of production, a supremacy that is like one of the wild artistic talents, irrational, only half- conscious, uncontrolled, out of balance with intelligence and other impulses, there derives, for the United States, a powerful urge toward a crude, narrowly conceived economic imperialism.

Driven by the potential of their mass production factories, the directors of the American economy would like to imagine the world as an open field, waiting for the rain of American goods and machines and money.

They can provide all, they dream, for all the world, and they do not need any help from other bungling, ineffective nations, a Germany or England or Japan.

The world, all the world, should be the vast market for American goods and machines and the source of certain desirable supplies. What a blessing it would be to the world!

If only it were not for the narrowness of foreign business competitors, and the blindness of generals and politicians at home as well as elsewhere, whose careers seem to be a wilful plot against rational and efficient production.

But the politicians and generals remain, and the ability to organize mass production is not a sufficient qualification for the proper conduct of the affairs of a great world power.

Human society is more than factories, weighty as is the influence of the factories on society as a whole.

And when we leave the premises of the factories, the American, there so seemingly mature and triumphant, appears as a gawky adolescent.

For this social immaturity, the circumstances of the nation's history provide an explanation.

The United States began only three centuries ago, as a colonial offshoot of Western Civilization.

During more than two of these centuries, its energies were concentrated on the comparatively primitive task of conquering a natural wilderness.

It was removed, in those generations, from the culture and learning of the civilization of which it was nevertheless a part, and from which its historical life was drawn. Its good fortune, moreover, hindered its normal cultural growth, like a gross boy too pampered and sheltered by a foolish mother.

Its rich material resources, its continental self-sufficiency, its geographical isolation until the present age, were curtains hiding from it the way of the world.

The natural wilderness was subdued, a nation was formed, a matchless economic machine constructed, but there was no art of its own, no music, no literature, no great philosophy or religion, none of those signs of an inner and deeper wisdom.

The foolish, sheltering mother is now dead, killed by the conseqences of scientific technology. The walls of the continental home are down.

The untrained adolescent must act on the world arena, not with an obscure apprenticeship but as a spotlit, featured star.

The result is a kind of schizoid split; the accomplished, confident technician of production is fused with a crude and hesitant semibarbarian.

Let us consider, as a symptom of this schizoid adolescence, the attitude of our soldiers at the end of the recent war. Most accounts agree that it was summed up in a single objective: to go home, to Mother, the Best Girl, a local job, and the corner drugstore or saloon. Emotionally the wish is understandable and sympathetic.

But rationally - it should be plain that such an attitude on the part of its young men is incompatible with the objective requirements of a world power. This was not the attitude of the young men of the Athens of the 5th century B.C., or of the Rome of the late Republic and the Empire, or of the Moslems of the 8th century, or of modern Holland and England and France. The young men of a world power must be ready to act in the world, to seek their career and its fruition in far places.

Power is not abstract, nor is it adequately embodied in bills of exchange, or mere material commodities.

As United States power stretches out to Brazil or Africa or China or Europe or the Near East, it must be concretized in men and their institutions, in soldiers and engineers and administrators and intelligence agents, in factories and airfields and plantations and railroads.

It is contemptible to blame the young soldiers for their provincial attitude, to condemn them, as has been not infrequently done, for cowardice or shirking.

It is the nation, not the soldiers alone, that is unprepared.

It was the members of Congress, not the soldiers, who showed real cowardice and blindness when they responded to the complaints of the soldiers not by pointing out to them the re- sponsibilities of world power but by yielding to the homesickness, and seeking demagogically to gain a few cheap votes by joining in the clamor to bring the boys home at whatever cost to the interest of the nation — and of the world.

The same provincialism, flatly counter to the needs of world power, is reflected in the educational system.

There are few Americans who can speak even tolerably well a foreign language, and fewer still who bother to learn intimately another nation's culture.

Until very recently, there were only one or two schools that trained students for international careers in diplomacy or business.

Even the New York Times, the most internationalist of the country's journals, advocates as the educational reform most to be desired a new concentration on United States history — at the very moment when what is required is an understanding of world history.

Equally revealing is the nation's attitude toward its armed services. Responsible world power must be based finally upon military strength.

The nation, daily and unavoidably intervening all over the world — from Argentina to Spain to Iran to Manchuria — suffers an extended internal crisis over the perfectly obvious question of a renewed Draft Law, a necessity which is so much accepted by all other nations as to be not even subject for debate.

This failure to take the armed services seriously has, of course, a long historical background. The seriousness was, in fact, not required in the past, because, on the one hand, possible wars developed slowly, with geography an adequate first line of defense; and, on the other, the nation did not have extensive permanent commitments throughout the world.

The carry-over of this attitude into the new period, when all has changed, when the United States is one of the two decisive world powers, is another sign of the nation's adolescent schizo- phrenia.

Psychically, the United States does not want to admit to itself that it is not a child any longer, but a grown-up man.

We may note similar characteristics in the nation's economic conceptions (as distinguished from its practical abilities at economic production).

The owner or manager of a factory is delighted to sell his goods abroad at a profit, and from his standpoint there the whole matter ends.

He doesn't want to reflect that if he and others like him sell abroad, then someone inside the country must also buy from abroad. (IN 1947) He hasn't learned that for a mature world power it is even more necessary to receive than to give.

Congressmen and busi- nessmen alike argue about loans to Britain or France or China as if they v/ere niggling credits arranged by a store at a local bank, in- stead of conceiving them in their actual meaning as instruments of world policy. Ship owNers and airways companies haggle over a foreign contract - to make it net a few more dollars, without any concern for the fact that they might be driving a potential ally into the network of the world opponent.

I have been mentioning a few symptomatic illustrations of what I have called the immaturity of the United States.

STOPped 6-13-2022

This "immaturity" may be described more abstractly as a form of what sociologists call "cultural lag"; specifically, the persistence of habits, attitudes, ideas, customs, and to some extent institutional structures, appro- priate enough to the United States of the 19th century, into a new period where the actual position of the United States has com- pletely changed, and where these persisting habits, attitudes and ideas are incongruous and stultifying. The United States, become in fact a world power, potentially the greatest world power, cannot function properly as a world power because it still conceives itself and the world through the medium of ideas suited to what was, in reality, a province, out of the main stream. The illustrations could readily be multiplied. I propose, however, to restrict myself to one further instance, the most important of all, and the one most directly relevant to the subject matter of this book: the immaturity of the United States in political understanding. Three features of United States foreign policy during the past £vc years (though they are not confined to that interval) must have struck nearly every reflective observer. First, the policy abruptly shifts, without any adequate motivation. The United States forces Argentina into the United Nations, then takes the lead against Argentina by publishing the Blue Book on Peron; the pubHc is com- pelled to accept Tito, then the effort is made to help Mikhailovitch at his trial, and thereby to injure Tito; in China there is a flip-flop ■every few months; Soviet-dominated Poland is recognized at the same time that anti-communist exile Polish troops are aided; and so on. Second, the United States has not been securing political re- sults commensurate with its material strength. After all the con- ferences, Teheran or Yalta or Potsdam or London or Paris, it always turns out that the United States has made the significant conces- sions. This feature is the more striking in comparison to the habit of Soviet diplomacy, during these same years, to get results far greater than would seem to follow from its material strength. Even when the Soviet Union was on the edge of military defeat, it could still win political victories. Third, there is a peculiar ineptness about United States political actions. The political representatives are al- ways making mistakes, getting mixed up, getting lost in procedure, having to retract and start over. These features are all related to the fact that the United States does not have at its disposal among its citizens, governing or gov- erned, a trained understanding of' the field of politics in its more general sense, or, in particular, of contemporary world politics. Many of the poHtical representatives of the United States do not know either what they are doing or what they are up against; they do not even know, usually, what the problems are. The prevailing conceptions of politics in the United States have two chief sources, both extending back to the early years of the unified nation. One is the abstract, empty, sentimental rhetoric of democratic idealism, as established for us first by Thomas Jeffer- son. This is for speeches, conscience-soothing, and full-dress occa- sions. The other is the ward-heeling, hotel-and-saloon, spoils-system, machine practices, put on a working basis first by Jefferson's party colleague and first vice-president, Aaron Burr. This is the traditional American combination, holding as much for the Republican as for the Democratic Party. The amalgam, under Franklin Roosevelt, of the "idealistic" New Dealers with the "vicious city machines," so puzzling to many liberal commentators, is in the standard American style, and is to be found just as plainly functioning in Jefferson's election, through Burr, in 1800. Jeffersonian rhetoric has no connection with reality, and I shall not, therefore, be further concerned with it. When it is taken seri- ously, as it is not by many of those who most frequently employ it, it prohibits the understanding of political events. American machine politics, and the ideas corresponding to ma- chine politics, are remarkably effective within a limited range of political action, especially under more or less stable social conditions.

They can take over and keep control of a city administration or a State government, or swing the outcome of the national nominating convention of one of the political parties. They can, within their restricted sphere, suitably reward political friends and punish enemies. When, however, either the scale of political action sufficiently expands or the social conditions underlying politics enter a period of crisis, the machine conceptions are no longer adapted. Great nations, with a tradition and a culture, do not operate in terms of quashed parking tickets, building contracts, and soft jobs in the local courthouse. To deal successfully with them on a world scale, it is necessary to know something about world geography and eco- nomics — and even religions and morals, and about the history and behavior of civilizations. Moreover, in times of crisis, the control of the movements of the masses cannot be won by cigars and hand- shakes and postmasterships. The masses become subject to the in- fluence of ideas, of world-shaking myths, of vast, non-rational impulses. Here, also, the usage of the educational system is instructive.

In United States educational institutions, from primary school to uni- versity, politics is taught under such headings as "Civics" or "Gov- ernment."

The courses bolster the usual rhetoric

with sterile charts of outward governmental forms — constitutions and bureaus and uni- or bi-cameral parliaments and departments and councils.

For practical training, students are taught case-work technique in social service, and how to become a Grade 8 civil servant.

We seldom find courses offered in world political history and its correlated fields, in geopolitics, world economics, military history.

In the United States, the "practical politician" despises the men of learning in the political sciences — for there are a few; and the men of learning, blocked from contact with the springs of power, become academic and sterile. We live in what Lenin correctly described as an "era of wars and revolutions," in the midst, indeed, of a great world revolution.* A distinguishing and all-important development of this era has been the rise of the totalitarian political movements, of the essentially similar though variously named Nazi, fascist, and communist varieties. Nowhere is the political illiteracy of Americans more fully and disastrously shown than in their lack of understanding of these totalitarian movements. Many of our political leaders believe that the totalitarian parties, though somewhat strange and "foreign," are fundamentally similar to our own Democratic and Republican parties, -- those loose, shifting aggregations of millions of diverse- minded men and women, held together by vague sentiments, vaguer traditions, and the business of office-seeking. When General Patton slowed up in his de-Nazification of the Third Army's zone in Ger- many, he explained that after all the difference between Nazis and anti-Nazis was pretty much like that between Democrats and Republicans at home. He was relieved of his command; but his error was no greater than that of Roosevelt or Hull or Stettinius or Byrnes or Acheson or Wallace - when, all over the world, they accepted without protest the inclusion of the communists among the "democratic parties" that should be permitted to function with full freedom in liberated or conquered nations, and when they welcomed commu- nists into reconstituted governments. In China, indeed, the United States government compelled Chiang Kai-shek to propose, in the autumn of 1945, the inclusion of the Chinese communists in the Chinese government.

[ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Totalitarianism ]

SOURCE: https://online.ucpress.edu/cpcs/article-abstract/53/1/13/107200/Theory-behind-Russian-Quest-for-Totalitarianism?redirectedFrom=PDF

March 2020

RESEARCH ARTICLE| MARCH 01 2020

Theory behind Russian Quest for Totalitarianism. Analysis of Discursive Swing in Putin's Speeches

Communist and Post-Communist Studies (2020) 53 (1): 13–26.

https://doi.org/10.1525/cpcs.2020.53.1.13

These totalitarian movements, with their steel discipline, their

monolithic structure, their cement of terror, their rigid and total

ideology, their pervasion of every aspect of the lives of their mem-

bers, are of a species totally different from what we are accustomed

to think of as "political parties."

No wonder the United States political representatives are constantly surprised by the behavior of

the Soviet representatives at every conference, just as they were always surprised by the Nazis.

Our diplomats believe that they are

bargaining with other men who, though tough and shrewd, are of

a similar kind to themselves, and who operate according to the same

underlying rules.

For the Soviet men, the bargaining is the lesser detail.

They are there to use the conference as a forum from which to speak to the masses,

and as a device not for gaining agreement with, but for promoting the destruction of, their fellow-conferees.

Gromyko's rude behavior at the Security Council is unintelligible to Byrnes;

but Byrnes' vacillating behavior, unfortunately, is not unintelligible to Gromyko.

The low level of political knowledge in the United States is shown

(also) by the books, articles, speeches, editorials and columns on political affairs.

Here direct comparison can be made, and it is safe

to say, I think, that our [United States] level is lower than that of any other nation.

To an informed Russian or Englishman or Chinese or Brazilian, it

must seem incredible that tens of millions of the citizens of the

United States guide their political sense by columnists and radio

speakers educated by years of scandal-mongering, sports writing, or

cigar salesmanship; and try to find out what is happening in the

world by reading the careless notes of journalists who consider themselves qualified

as "political analysts" because they call famous men [1947] by

their first names and know the fashionable bar in each capital.

It would be absurd to believe that a mere increase in political

understanding could solve the catastrophic political problems that lie ahead.

In spite of Bacon, knowledge is not of itself power.

But - ignorance is weakness, because ignorance is not able to direct

whatever resources may be available toward the goals that may be selected.

Nonsense is a safe luxury only in times more tranquil than ours.

The purpose of this book may be simply stated. I [ James Burnham ] propose to analyze, in its primary and most fundamental lines, the world political situation as it exists in this period following the conclusion of the Second World War; as it exists in reality, not as it is distorted in wishful dreams or in the lies of propagandists. I propose, further, in terms of the actual situation, to examine the alternatives of political action which are at the disposal of the United States. < go to Contents>

2. Is It Really One World?

( https://archive.org/details/struggleforworld00burn/page/n7/mode/2up )

WENDELL WILLKIE, with an enthusiasm touched off by the

wonders of modern air transport, popularized the phrase, "one

world." The complex o£ feelings and ideas associated with the phrase

were not, however, Willkie's discovery. They have a longer history.

It is worth while to be clear about this question of the unity of

the world, since more is at stake than a fruitful subject for after-

dinner conversation or election campaigns. To many, there seem to

follow, from the belief that the world is one, certain political con-

clusions of great import. If the world is one, they argue, then it can

and ought properly to be politically united; then there can, and

should be, just one world government. In order to unite the world

in a single world government, all that is necessary is to make known

to the peoples of the world this fact that their world is one.

Is it true that the world is one ? Or rather, since this first quesdon

is ambiguous, is a way of confusing several different and independent

questions, let us put it : in what sense or senses is the world one ? in

what sense or senses is it many? In both cases, the answer must be

in terms that are relevant to the problems of world politics. The fact

that the world is one in an astronomical sense, as a single planet

located in the gravitational field of a definite star, is not of political

importance.

The first expression, in the West, of the notion of the unity of the

world was, according to tradition, by Alexander the Great, who

therein went beyond the philosophic ideas of his tutor Aristotle. It

was developed further by the Stoics of the Roman Empire, by

Dante, partly under Stoic influence, and by the medieval philoso-

phers, with their doctrine of a universal "natural law." Kant, in his

moral philosophy, gave it a new variation; and it reappears today

among the beliefs of many internationalists.

The oneness of the world, as interpreted by the core of meaning

shared in this lineage, extended over 2300 years, and to be found

also in Confucius and in the earliest, non-supernatural form of

Buddhism, is a secular philosophic conception that all men are one

because they share in a "common humanity." Whatever the diver-

sities in their talents or circumstances, all men are subject to the

laws of the universal cosmos, all men have reason, all men are moral

beings, equally able to exercise moral will and equally bound by

moral duty. "World humanity," "the world community," therefore,

are not empty abstractions, but are phrases which sum up the ob-

jective metaphysical reality of a single universal human nature.

In recent years, this philosophic conception has been given a more

naturalistic, empirical slant. Emphasis is sometimes put not so much

on reason, moral will, and natural law that men are, in some com-

plicated metaphysical manner, presumed to share, as on the basic

biological and psychological needs, desires and impulses that they

undoubtedly do share : needs for food, sex and shelter, the desire for

some sort of security, the impulse toward sociality.

A content similar to that of these secular conceptions is to be

found, transferred into religious language, in the ideas of the great

world religions, particularly in Christianity, Hinduism and Bud-

dhism. In Christianity this is summed up in the New Testament

doctrine of "the Fatherhood of God and the Brotherhood of Man."

Since God is the Creator and Father of all men equally, since our

being is alike derived from Divinity, we are therefore all brothers.

This, then, is the first specifiable meaning, or rather set of mean-

ings, that can be given to the phrase, "one world." The world is one

because all men share a common humanity, whether that humanity

is interpreted in naturalistic, metaphysical or religious terms. What

bearing, then, does the oneness of the world, so understood, have

upon the cold historical problems of world politics in our time?

The answer, unfortunately, is that it has almost no bearing at all.

Whatever common humanity men may have, they must have had

it from the beginning. Men have existed on the earth for at least

several hundred thousand years, and probably for several million.

Their common humanity has never prevented them from always

being divided, from always fighting, killing, torturing and oppress-

ing each other. The very philosophers who proclaimed the meta-

physical doctrine have been conspicuous in the fighting and the

torturing; the religions which profess the Fatherhood o£ God have

inspired among the fiercest of the wars and persecutions; the fash-

ionable naturalists of common humanity in our own time have not

been backward in defending the saturation bombing of helpless

cities, where common humanity was thoroughly disintegrated in

common.

Experience does not, then, suggest that common humanity has

had much effect in contributing to the historical goal of one world

community. The trouble with the doctrine is, first, that in its selec-

tion of certain common factors from the totality of human nature

it neglects many less desirable but equally universal factors, such as

man's impulse to destruction and pain as well as to fraternity, his

need for hate, his desire for domination, in short his irrationality,

which is at least no less plain than his reason. Second, the doctrine,

having decided on its common factors, fails to note that, in concrete

reality, these are inextricably bound up with many other factors,

both common and special, both universal and particular: with the

other, neglected common factors, and with all the particulars of

tribe, family, city, nation, property relations, language, wealth and

poverty, customs and taboos, material resources, science and religion

and technology and art. What men actually do in history, and

notably the conflicts they get into with each other, are determined

not so much by the abstracted factors which they have in common

as by the specific circumstances of place and social structure and

time, wherein their interests diverge and their objectives clash. The

humanity common to a Soviet commissar, a Trobriand native, a

Midwestern small farmer, and a Spanish Jesuit is a rather pale resi-

due, a not very substantial foundation for the construction of one

world.

Moreover, the common needs and impulses that men have — for

food, shelter, women, pre-eminence, wealth, pleasure — ^far from

invariably bringing them together in brotherhood, are more usually

sources of their mutual struggle. When there is not enough food to

go around, reason and the moral will have never proved adequate

to the task of deciding who gets what. The nomads of steppes be-

come arid through climatic change descend on the plain, with as

much and as little attention to the claims of moral duty as die house-

wives who throw themselves into the frenzy o£ the black market.

It would, nevertheless, be wrong to dismiss altogether the doctrine

of common humanity and the brotherhood of man. Taken as a

description of what men have been and are, of how they behave, it

is distorted and even dangerously false. Projected as a guiding ideal,

as a goal and purpose, the doctrine has not only a splendid nobility,

so wonderfully expressed in those passages of St. Matthew where

Christ corrects the jealous separatism of the Scribes and Pharisees;

but it has also, through the loyalty of those who believe in the ideal,

a chance of influencing, toward the goal of brotherhood which it

states, the course of history.

It is not sentimental, but simply human, to have ideals. What is

sentimental, and what so often leads to disaster, is to confuse ideals

with present facts. Men are in fact not one but divided, not rational

in their actions but predominantly irrational, not filled with love

only but also with selfishness, not good but a strange mixture of

evil and good. The facts remain, whatever words we use. But men

can become less divided; and even if the hate and irrationality and

evil cannot be eliminated, their consequences can, perhaps, be made

less terrible. We rightly honor the ideal of common humanity. How-

ever far it is from solving, or even helping us much in solving, the

problems of today, it remains a hope, and the best hope, for tomor-

From the time of Karl Marx, the notion of one world has been

given another, very different interpretation, an interpretation ac-

cepted by many who are not at all Marxists. The world has not in

the past been one, the Marxists say, but it has become potentially

one — will, they would say, inevitably soon become one — through

the results of modern technology. Machines and mass production,

rapid transportation and communication, world-wide economic in-

terdependence through the world-wide division of labor and re-

sources, the spread of science and its applications, all these have so

linked all parts of the world together, so reduced the time and space

dimensions applicable to human society, that the world is today as

intimate a community as a county was a thousand years ago. When

these facts are recognized, or merely through their effect even if

unrecognized, the world as a whole will necessarily be organized,

socially and politically, into a single world state or society, so that

its political form will come into balance with its technological base.

This Marxian conclusion rests upon an assumption drawn from

the Marxian theory of history. According to the theory, the nature

of human society and the process of historical change depend "in

the final analysis" (to use Engels' ambiguous words) upon the

development of technology ("the means of production," in Marxian

language). In the long run, everything else, property relations, class

divisions, political organization, philosophy, art, morality and reli-

gion, follow causally from the state of technology as applied in the

means of production. Therefore, Marxists reason today, since a single

basic technology, a single means and method of production, are

now world-wide in extent and influence, it follows that government

(along with everything else) is, or is ready to be, world-wide. Man-

kind has become one because mankind as a whole now depends

upon a single means and method of production.

This Marxian doctrine is in part true, and I shall 'separate out its

truths before proceeding to state its errors.

Through scientific technology, factories and machines and assem-

bly lines, and an extreme division of labor. Western Civilization*

has constructed the extraordinary mechanical appliances and the

remarkable method of production with which we are all familiar.

These appliances, especially during the past century, have been spread

into all parts of the earth. For the use of the Western productive

plant, raw materials of many kinds, agricultural and mineral, have

likewise been drawn from all parts of the earth. Some regions —

notably Japan, Russia, and sections of such countries as China, India

and Turkey — not themselves part of Western Civilization have even

borrowed the method of production itself, and are turning out on

their own account the mechanical appliances.

We must further note that historical geography depends upon

* By "Western Civilization" I refer in this book to that civilization whose original

home was in the European peninsula, whose traditional religion has been Christianity,

and whose historical career began at the end of the Dark Ages that followed the col-

lapse of Hellenic Civilization.

... an Einsteinian rather than a Newtonian function; that is, upon a

combined space-time function. The devices for rapid communication

and transportation, and for long-distance warfare, have historically

speaking greatly reduced the size of the earth. The historical, polit-

ical distance between two places depends primarily upon how long

it takes to get from one to the other, either in person, or in influence,

as by the proxy of a message or a bomb. Today it takes much less

time for a man to go from New York to Moscow than it took him

150 years back to go from New York to Boston; and it takes in-

comparably less time for a radio message or a rocket to travel either

distance.* Therefore it is correct to say that, in certain respects at

least, the world today is a community as geographically intimate as

a county a thousand years ago.

A conclusion of great importance does follow from these truths.

They do not prove that the world and its civilization are one, or

that a world community is inevitable; but they show that the ad-

ministration of the world, or most of the world, as a single state is

now technically possible. There is no longer any insuperable tech-

nical obstacle to a degree of integration in armed power, police,

courts, finances and economy sufficient to constitute a unified world

state.

From this positive conclusion, which I shall later use in positive

analysis, we may turn to the errors in the Marxian doctrine. Of

these, there are principally two. First, the existing facts are over-

stated. Though it is true that the mechanical appliances of Western

Civilization are found all over the earth, they are in many regions

far from abundant, in not a few so rare as to make hardly a ripple

in the sea of the local culture. Airplanes have by now been seen,

probably, by most human beings; but there are comparatively few

places where airplanes have become part of ordinary daily life. A

* This fact alone shows the absurdity o£ those who argue that there can be two

great nations today — the United States and the Soviet Union, for example — ^with no

potential basis of conflict because they have no "points of contact": that is, their

borders do not meet on a conventional map. Today the real borders of all nations —

the limits of their interests — all overlap.

... radio or an electric iron or a light bulb is still a magical sensation

among well over half the peoples of the earth. If we study economic

maps of the distribution of railroads or electric power plants or auto-

mobiles or telephones, what impresses us is not that they diffuse the

earth, but quite the contrary, that most of the world is almost en-

tirely without them.

If we consider the advanced Western means of production, we

find that their distribution is even more narrowly limited. The maps

show only a few major concentrations: in the United States, in Eng-

land, in certain areas of the Soviet Union, in Japan and the adja-

cent Chinese coast, and in part of Continental Europe; and the

Second World War has considerably reduced the last two. Else-

where, it is only in a few seacoast city areas in India, Brazil, Argen-

tina, Australia and perhaps one or two other nations that we find

significant quantities of the typical Western means of production

— the factories, mills, power plants.

The mechanical appliances of the West are not, therefore, literally

present everywhere in the world. The most that we can correctly

say is that their power and influence are felt, directly or indirectly,

everywhere in the world.

The second Marxian error is deeper. It is the error in the assump-

tion drawn from the general theory of history, the error in the belief

that technology is the sole determinant of the nature and process of

history and civilization. Technology is unquestionably one of the

decisive causal forces in history, and in the history of Western

Civilization, especially since the Renaissance, it has been perhaps

more influential -than any other causal force; but in the history of

civilizations in general it must be reduced to merely one among

several determining influences. Climate, custom, institutional forms,

religion, moraUty, even intelligence and individual genius, all have

at least a relative autonomy as historical forces. The nature and fate

of civilizations is the resultant of the interaction of all of these, and

still others, with each other, and with, of course, technology as well.

We who belong to Western Civilization have our vision distorted

by a parochial blindness. We assume the identity of mankind as a

whole with ourselves. All that we can see of the peoples of the earth

is ourselves — the "civilized" — and a dim outer fringe of "natives."

And since we are peculiarly distinguished by our technological

prowess, we further confound civilization with technology. Through

this narrow slit, this egocentrism, the world can appear as one, or

almost one. If, however, we try for a moment to lift and expand our

vision, if we get rid of the filters of Westernization and technology,

the map of the world falls into more profoundly varied contours.

The nations of Western Civilization are themselves, for that mat-

ter, bitterly and obviously divided, so bitterly that they have been

engaged during the present century in the effort, not without suc-

cess, to annihilate each other. They are divided in language, in

economic interest, in governmental forms, in the axioms of juris-

prudence. The fiercely divisive influence of nationalism is itself a

phenomenon of our age. Our kind of nationalism arose in conjunc-

tion with the French Revolution, and today it shows few signs of

abating. It is a remarkable fact that during the Second World War

the effective resistance in Europe to both Nazism and communism

turned out to be nationalist in motive. Neither freedom in the ab-

stract nor "class war" nor "United Europe" nor "World Govern-

ment" proved to be the rallying ideas of the undergrounds and the

resistance movements. It was the idea of "France," of "Poland,"

of "Greece."

If there are these divisions within Western Civilization, how much

more profoundly divided, then, is the world as a whole, where there

simultaneously exist, along with Western Civilization, at least four

other distinct civilizations — the Far Eastern, the Islamic, the Hindu,

and the Orthodox Christian — together with the remains of several

earlier civilizations, and even a number of surviving primitive cul-

tures ?

The misleading feature in the social environment has been the fact

that, in modern times, our own Western Civilization has cast the

net of its economic system round the World and has caught in its

meshes the whole living generation of Mankind and all the habitable

lands and navigable seas on the face of the Planet. . . .

[Western observers who believe in "the unity of civilization," in

"one world"] have exaggerated the range of the facts in two direc-

tions. First, they have assumed that the present more or less com-

plete unification of the World on a Western basis on the economic

plane and the large measure of unification on the same basis which

has been accomplished on the political plane are together tantamount

to a perfect unification on all planes. Secondly, they have equated

unification with unity. . . .

[Their] vision of the contemporary world must be confined to the

economic and political planes of social life and must be inhibited

from penetrating to the cultural plane, which is not only deeper

but is fundamental. While the economic and political maps of the

World have now been "Westernized" almost out of recognition, the

cultural map remains today substantially what it was before our

Western Society ever started on its career of economic and political

conquest. On this cultural plane, for those who have eyes to see, the

lineaments of the four living non-Western civilizations are still clear.

Even the fainter outlines of the frail primitive societies that are being

ground to powder by the passage of the ponderous Western steam-

roller have not quite ceased to be visible. How have our historians

managed to close their eyes lest they should see? They have simply

put on the spectacles — or the blinkers — of their generation; and we

may best apprehend what the outlook of this generation has been

by examining the connotation of the English word "Natives" and

the equivalent words in the other vernacular languages of the con-

temporary Western World.

When we Westerners call people "Natives" we implicidy take all

the cultural colour out of our perceptions of them. We see them as

trees walking, or as wild animals infesting the country in which

we happen to come across them . . . Their tenure is as provisional

and precarious as that of the forest trees which the Western pioneer

fells or that of the big game which he shoots down. And how shall

the "civilized" Lords of Creation treat the human game, when in

their own good time they come to take possession of the land which,

by right of eminent domain, is indefeasibly their own? Shall they

treat these "Natives" as vermin to be exterminated, or as domesti-

cable animals to be turned into hewers of wood and drawers of

water? .... Evidently the word ("Native") is not a scientific term

but an instrument of action ... It belongs to the realm of Western

practice and not of Western theory; and this explains the paradox

that a classificatory-minded society has not hesitated to apply the

name indiscriminately to the countrymen of a Gandhi and a Bose

and a Rabindranath Tagore, as well as to "primitives" of die lowest

degree of culture, such as the Andaman Islanders and tlie Australian

... Blackfellows, For the theoretical purpose of objective description,

this sweeping use of the word makes sheer nonsense. For the prac-

tical purpose of asserting the claim that our Western Civilization is

the only civilization in the World, the usage is a militant gesture.*

Wendell Willkie, in his hurried trip, visited large cities, factories,

airports and government offices. He talked to factory managers, gen-

erals, bureaucrats and high administrators, who were besides anxious

for favors, through a good report, from the United States. Not un-

naturally Willkie saw that world as one. But it does not take a

very long trip in from the seacoast of India or New Zealand or

China or Arabia or Africa or Burma or Ceylon to remind those who

are willing to see that culturally the world is not one but many. It

does not, indeed, take a trip longer than that to our local museum

or library, where songs and pictures and statues and symbols and

religious books will offer the same evidence. The diversity, moreover,

is not just a surface paint. There are even, hard as it is for a West-

ern mind to understand it, "natives" — of China and India and

Morocco and Turkey — who not only have no automobiles and bath-

tubs and radios but who do not want them.f

We may summarize the analysis, up to this point, of "one world":

The world is potentially one in the light of a possible ideal of

brotherhood, of common humanity. The world is actually one, at

least at a certain level, through the direct or indirect influence of a

particular technology and method of economic production. Politi-

cally, and, most deeply of all, culturally, the world is many.

* Quoted by permission from A Study of History, by Arnold J. Toynbee, Vol. I,

I, C, III, {b), pp. 150-153, published by the Oxford University Press (London) on

behalf of the Royal Institute of International Affairs. In this chapter, and in

Chapter 4, I have drawn considerably from this great work.

t Toynbee, op cit., recalls "the story of the Sharif of Morocco who, returning

home after a visit to Europe . . . , was yet heard to exclaim, as he sighted the

Moroccan coast: 'What a comfort to be getting back to Civilization!' When our

great-grandchildren make the same remark as their ship enters the Solent or the

Mersey, will the joke be published in the comic papers of China and — Morocco?"

I have dealt so far in this chapter with long-term phenomena: of