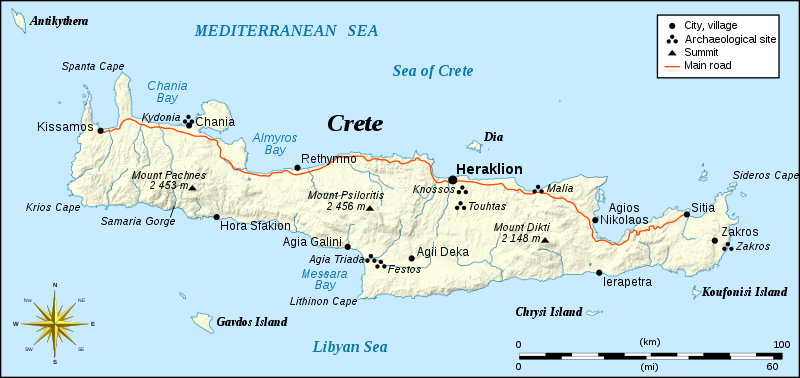

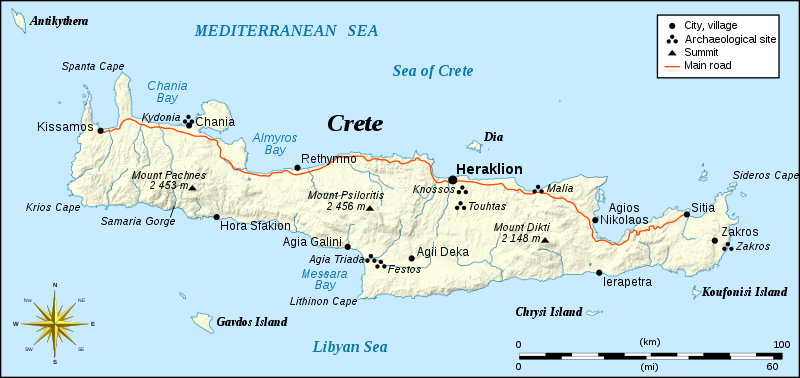

< https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Crete_integrated_map-en.svg

< https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Crete_integrated_map-en.svg < home > 4-5-2021

Source: https://archive.org/stream/TheStoryOfCivilization02/The%20Story%20of%20Civilization%2002_djvu.txt

Full text of "The Story Of Civilization 02"

See other formats

THE STORY OF CIVILIZATION (tm) Ver. 4.8

2: The Life of Greece Durant, Will

THE STORY OF CIVILIZATION - VOLUME TWO

THE LIFE OF GREECE

1939

Being a history of Greek civilization from the beginnings,

and of civilization in the Near East from the death of Alexander,

to the Roman conquest; with an introduction

on the prehistoric culture of Crete -by Will Durant

h https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Crete#Prehistoric_Crete

"... In 2002, the paleontologist Gerard Gierlinski discovered what he claimed were fossil footprints left by ancient human relatives 5,600,000 years ago, but the claim is controversial.[2]

[ https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/longform/human-footprints-greece FEBRUARY 2018 ]

Excavations in South Crete in 2008–2009 revealed stone tools at least 130,000 years old.[3][4] This was a sensational discovery, as the previously accepted earliest sea crossing in the Mediterranean was thought to occur around 12,000 BC.

The stone tools found in the Plakias region of Crete include hand axes of the Acheulean type made of quartz. It is believed that pre-Homo sapiens hominids from Africa crossed to Crete on rafts. [5][6][better source needed]

https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/16/science/16archeo.html < [5]

https://www.wired.com/2010/01/ancient-seafarers/ [6]

< https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Crete_integrated_map-en.svg

< https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Crete_integrated_map-en.svg

In the neolithic period, some of the early influences on the development of Cretan culture arise from the Cyclades and from Egypt; cultural records are written in the undeciphered script known as "Linear A".

The archaeological record of Crete includes superb palaces, houses, roads, paintings and sculptures. Early Neolithic settlements in Crete include Knossos and Trapeza.

HHHHH  HHHHH ------- > EZRA

HHHHH ------- > EZRA

For the earlier times, radiocarbon dating of organic remains and charcoal offers some dates. Based on this, it is thought that Crete was inhabited from about 130,000 years ago, in the Lower Paleolithic,[7] perhaps not continuously, with a Neolithic farming culture from the 7th millennium BC onwards. The first settlers introduced cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, and dogs, as well as domesticated cereals and legumes.

The native fauna of Crete included pygmy hippo, pygmy elephant Paleoloxodon chaniensis, dwarf deer Praemegaceros cretensis, giant mice Kritimys catreus, and insectivores as well as badger, beech marten and Lutrogale cretensis, a kind of terrestrial otter. Large mammalian carnivores were lacking; in their stead, the flightless Cretan owl was the apex predator. [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cretan_owl ]

Most of these animals died out at the end of the last ice-age. Humans played a part in this extinction, which occurred on other medium to large Mediterranean islands as well;, for example, on Cyprus, Sicily and Majorca.

Remains of a settlement found under the Bronze Age palace at Knossos date to the 7th millennium BC. Up to now, Knossos remains the only aceramic site. The settlement covered approximately 350,000 square metres. The sparse animal bones contain the above-mentioned domestic species as well as deer, badger, marten and mouse: the extinction of the local megafauna had not left much game behind.

Neolithic pottery is known from Knossos, Lera Cave and Gerani Cave. The Late Neolithic sees a proliferation of sites, pointing to a population increase. In the late Neolithic, the donkey and the rabbit were introduced to the island; deer and agrimi were hunted. The Kri-kri, a feral goat, preserves traits of the early domesticates. Horse, fallow deer and hedgehog are only attested from Minoan times onwards. [ https://smarthistory.org/ancient-mediterranean/the-palace-at-knossos-crete/ ]

..."

Copyright (C) 1939 by Will Durant :: Copyright renewed (C) 1966 by Will Durant

Exclusive electronic rights granted to World Library, Inc. -- by The Ethel B. Durant Trust, William James Durant Easton, and Monica Ariel Mihell.

Electronically Enhanced Text (c) Copyright 1994 World Library, Inc.

DEDICATION -- TO MY FRIEND MAX SCHOTT

MY purpose is to record and contemplate the origin, growth, maturity, and decline of Greek civilization from the oldest remains of Crete and Troy to the conquest of Greece by Rome.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greece_in_the_Roman_era

Greece in the Roman era describes the Roman conquest of Greece and the period of Greek history when Ancient Greece was dominated by the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire (27 BC-AD 1453), commonly referred to as the Byzantine Empire after about AD 395. The Roman era of Greek history began with the Corinthian defeat in the Battle of Corinth in 146 BC. However, before the Achaean War, the Roman Republic had been steadily gaining control of mainland Greece by defeating the Kingdom of Macedon in a series of conflicts known as the Macedonian Wars. The Fourth Macedonian War ended at the Battle of Pydna in 148 BC and defeat of the Macedonian royal pretender Andriscus.

The definitive Roman occupation of the Greek world was established after the Battle of Actium (31 BC), in which Augustus defeated Cleopatra VII, the Greek Ptolemaic queen of Egypt, and the Roman general Mark Antony, and afterwards conquered Alexandria (30 BC), the last great city of Hellenistic Greece.[1] The Roman era of Greek history continued with Emperor Constantine the Great's adoption of Byzantium as Nova Roma, the capital city of the Roman Empire; in AD 330, the city was renamed Constantinople. Afterwards, the Byzantine Empire was in general a polity Greek in culture and language.

I wish to see and feel this complex culture not only in the subtle and impersonal rhythm of its rise and fall, but in the rich variety of its vital elements:

its ways of drawing a living from the land, and of organizing industry and trade; its experiments with monarchy, aristocracy, democracy,

dictatorship, and revolution; its manners and morals, its religious practices and beliefs; its education of children, and its regulation

of the sexes and the family; its homes and temples, markets and theaters and athletic fields; its poetry and drama, its painting,

sculpture, architecture, and music; its sciences and inventions, its

superstitions and philosophies. I wish to see and feel these

elements not in their theoretical and scholastic isolation, but in

their living interplay as the simultaneous movements of one great

cultural organism, with a hundred organs and a hundred million

cells, but with one body and one soul.

Excepting machinery, there is hardly anything secular in our culture that does not come from Greece. Schools, gymnasiums, arithmetic,

geometry, history, rhetoric, physics, biology, anatomy, hygiene, therapy, cosmetics, poetry, music, tragedy, comedy, philosophy,

theology, agnosticism, skepticism, stoicism, epicureanism, ethics, politics, idealism, philanthropy, cynicism, tyranny, plutocracy, democracy:

these are all Greek words for cultural forms seldom

originated, but in many cases first matured for good or evil by the

abounding energy of the Greeks.

All the problems that disturb us today- the cutting down of forests and the erosion of the soil; the

emancipation of woman and the limitation of the family; the

conservatism of the established, and the experimentalism of the

unplaced, in morals, music, and government; the corruptions of

politics and the perversions of conduct; the conflict of religion

and science, and the weakening of the supernatural supports of

morality; the war of the classes, the nations, and the continents; the

revolutions of the poor against the economically powerful rich, and of

the rich against the politically powerful poor; the struggle between

democracy and dictatorship, between individualism and communism,

between the East and the West- all these agitated, as if for our

instruction, the brilliant and turbulent life of ancient Hellas. There

is nothing in Greek civilization that does not illuminate our own.

We shall try to see the life of Greece both in the mutual interplay of its cultural elements, and in the immense five-act drama of its rise and fall.

We shall begin with Crete and its lately

resurrected civilization, because apparently from Crete, as well as

from Asia, came that prehistoric culture of Mycenae and Tiryns which

slowly transformed the immigrating Achaeans and the invading Dorians

into civilized Greeks; and we shall study for a moment the virile

world of warriors and lovers, pirates and troubadours, that has come

down to us on the rushing river of Homer's verse.

We shall watch the rise of Sparta and Athens under Lycurgus and Solon, and shall trace

the colonizing spread of the fertile Greeks through all the isles of

the Aegean, the coasts of Western Asia and the Black Sea, of Africa

and Italy, Sicily, France, and Spain.

We shall see democracy

fighting for its life at Marathon, stimulated by its victory,

organizing itself under Pericles, and flowering into the richest

culture in history; we shall linger with pleasure over the spectacle

of the human mind liberating itself from superstition, creating new

sciences, rationalizing medicine, secularizing history, and reaching

unprecedented peaks in poetry and drama, philosophy, oratory, history,

and art; and we shall record with melancholy the suicidal end of the

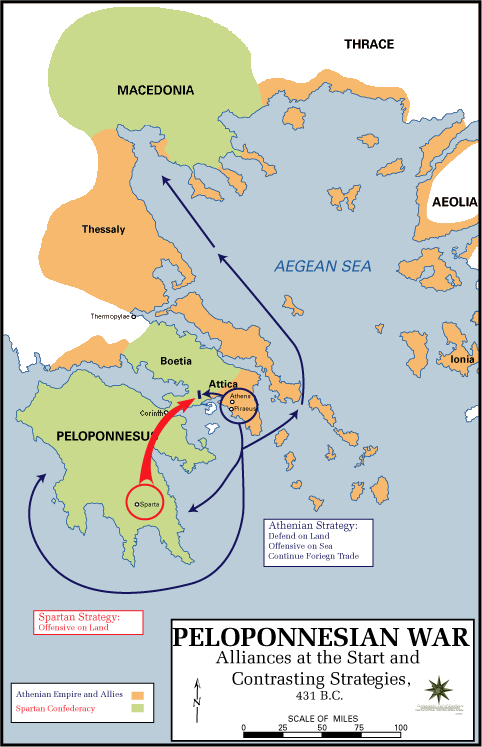

Golden Age in the Peloponnesian War.  < https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peloponnesian_War

< https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Peloponnesian_War

We shall contemplate the gallant effort of disordered Athens to recover from the blow of her

defeat; even her decline will be illustrious with the genius of

Plato and Aristotle, Apelles and Praxiteles, Philip and Demosthenes,

Diogenes and Alexander. Then, in the wake of Alexander's generals, we shall see Greek civilization, too powerful for its little

peninsula, bursting its narrow bounds, and overflowing again into

Asia, Africa, and Italy; teaching the cult of the body and the intellect to the mystical Orient, reviving the glories of Egypt in

Ptolemaic Alexandria, and enriching Rhodes with trade and art;

developing geometry with Euclid at Alexandria and Archimedes at

Syracuse; formulating in Zeno and Epicurus the most lasting

philosophies in history; carving the Aphrodite of Melos [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venus_de_Milo ], the

Laocoon, the Victory of Samothrace, and the Altar of Pergamum; striving and failing to organize its politics into honesty, unity, and peace; sinking ever deeper into the chaos of civil and class war;

exhausted in soil and loins and spirit; surrendering to the autocracy, quietism, and mysticism of the Orient; and at last almost welcoming those conquering Romans through whom dying Greece would bequeath to Europe her sciences, her philosophies, her letters, and her arts as

the living cultural basis of our modern world.

I am grateful to Mr. Wallace Brockway for his scholarly help at

every stage of this work; to Miss Mary Kaufman, Miss Ethel Durant, and

Mr. Louis Durant for aid in classifying the material; to Miss Regina

Sands for her expert preparation of the manuscript; and to my wife for

her patient encouragement and quiet inspiration.

I am deeply indebted to Sir Gilbert Murray and to his publishers,

the Oxford University Press, for permission to quote from his

translations of Greek drama. These translations have enriched English literature.

I am also indebted to the Oxford University Press for permission

to quote from its excellent Oxford Book of Greek Verse in Translation.

W. D.

NOTES ON THE USE OF THIS BOOK

1. This book, while forming the second part of the author's Story

of Civilization, has been written as an independent unit, complete in

itself. The next volume will probably appear in 1943 under the title

of Caesar and Christ - a history of Roman civilization and of early Christianity.

2. To bring the book into smaller compass, reduced type (like

this) has been used for technical or recondite material. Indented

passages in reduced type are quotations.

3. The raised numbers in the text refer to the Notes at the end of

the volume. Hiatuses in the numbering of the notes are due to last

minute curtailments.

4. The chronological table given at the beginning of each period

is designed to free the text as far as possible from minor dates and

royal trivialities. All dates are B.C. unless otherwise stated or

evident.

5. The maps at the beginning and the end of the book show nearly all

the places referred to in the text. The glossary defines all

unfamiliar foreign words used, except when these are explained where

they occur. The starred titles in the bibliography may serve as a

guide to further reading. The index pronounces ancient names, and

gives dates of birth and death where known.

6. Greek words have been transliterated into our alphabet

according to the rules formulated by the Journal of Hellenic

Studies; certain inconsistencies in these rules must be forgiven as

concessions to custom; e.g., Hieron, *02000 but Plato (n); Hippodameia, but Alexandr(e)ia.

7. In pronouncing Greek words not established in English usage,

a should be sounded as in father, e as in neigh, i as in

machine, o as in bone, u as in June, y like French u or German

u (with umlaut), ai and ei like ai in aisle, ou as in

route, c as in car, eh as in chorus, g as in go, z like dz in adze.

BOOK I: AEGEAN PRELUDE: 3500-1000 B.C.

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE FOR BOOK I

NOTES: All dates are approximate. Individuals are placed at their time of flourishing, which is assumed to be about forty years after

their birth; their dates of birth and death, where possible, are given in the index.

Dates of rulers are for their reigns. A question mark [?] before an entry indicates a date given only by Greek tradition.

B.C. 9000: Neolithic Age in Crete

3400-3000: Early Minoan, Helladic, Cycladic, I

3400-2100: Neolithic Age in Thessaly

3400-1200: Bronze Age in Crete

3000-2600: Early Minoan, Helladic, Cycladic, II

3000: Copper mined in Cyprus

2870: First known settlement at Troy

2600-2350: Early Minoan, Helladic, Cycladic, III

2350-2100: Middle Minoan, Helladic, Cycladic, I

2200-1200: Bronze Age in Cyprus

2100-1950: Middle Minoan, Helladic, Cycladic, II; first series of Cretan palaces

2100-1600: Chalcolithic Age in Thessaly

1950-1600: Middle Minoan, Helladic, Cycladic, III

1900: Destruction of first series of Cretan palaces

1600-1500: Late Minoan, Helladic (Mycenaean), Cycladic, I; second series of Cretan palaces

1600-1200: Bronze Age in Thessaly

1582: ? Foundation of Athens by Cecrops

1500-1400: Late Minoan, Helladic (Mycenaean), Cycladic, II

1450-1400: Destruction of second series of Cretan palaces

1433: ? Deucalion and the Flood

1400-1200: Late Minoan, Helladic (Mycenaean), Cycladic, III; palaces of Tiryns and Mycenae

1313: ? Foundation of Thebes by Cadmus

1300-1100: Age of Achaean domination in Greece

1283: ? Coming of Pelops into Elis

1261-1209: ? Heracles

1250: Theseus at Athens; Oedipus at Thebes; Minos and Daedalus at Cnossus

1250-1183: "Sixth city" of Troy; age of the Homeric heroes

1225: ? Voyage of the Argonauts

1213: ? War of the Seven against Thebes

1200: ? Accession of Agamemnon

1192-1183: ? Siege of Troy

1176: ? Accession of Orestes

1104: ? Dorian invasion of Greece

[ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/365_Crete_earthquake ]

AS we enter the fairest of all waters, leaving behind us the Atlantic and Gibraltar, we pass at once into the arena of Greek history. "Like frogs around a pond," said Plato, "we have settled down

upon the shores of this sea."

'02011 Even on these distant coasts the Greeks founded precarious, barbarian-bound colonies many centuries before Christ: at Hemeroscopium and Ampurias in Spain, at Marseilles

and Nice in France, and almost everywhere in southern Italy and Sicily.

Greek colonists established prosperous towns at Cyrene in

northern Africa, and at Naucratis in the delta of the Nile; their

restless enterprise stirred the islands of the Aegean and the coasts

of Asia Minor then as in our century; all along the Dardanelles and

the Sea of Marmora and the Black Sea they built towns and cities for

their far-venturing trade. Mainland Greece was but a small part of the

ancient Greek world.

Why was it that the second group of historic civilizations took form

on the Mediterranean, as the first had grown up along the rivers of

Egypt, Mesopotamia, and India, as the third would flourish on the

Atlantic, and as the fourth may appear on the shores of the Pacific?

Was it the better climate of the lands washed by the Mediterranean?

There, then as now, '02012 winter rains nourished the earth, and

moderate frosts stimulated men; there, almost all the year round,

one might live an open-air life under a warm but not enervating sun.

And yet the surface of the Mediterranean coasts and islands is nowhere

so rich as the alluvial valleys of the Ganges, the Indus, the

Tigris, the Euphrates, or the Nile; the summer's drought may begin too

soon or last too long; and everywhere a rocky basis lurks under the

thin crust of the dusty earth. The temperate north and the tropic

south are both more fertile than these historic lands where patient

peasants, weary of coaxing the soil, more and more abandoned tillage

to grow olives and the vine. And at any moment, along one or another

of a hundred faults, earthquakes might split the ground beneath [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/365_Crete_earthquake ]

men's feet, and frighten them into a fitful piety.

Climate did not draw civilization to Greece; probably it has never made a civilization anywhere.

What drew men into the Aegean was its islands. The islands were

beautiful; even a worried mariner must have been moved by the changing

colors of those shadowed hills that rose like temples out of the

reflecting sea. Today there are few sights lovelier on the globe;

and sailing the Aegean, one begins to understand why the men who

peopled those coasts and isles came to love them almost more than

life, and, like Socrates, thought exile bitterer than death.

But further, the mariner was pleased to find that these island jewels were

strewn in all directions, and at such short intervals that his ship,

whether going between east and west or between north and south,

would never be more than forty miles from land. And since the islands,

like the mainland ranges, were the mountaintops of a once continuous

territory that had been gradually submerged by a pertinacious

sea, '02013 some welcome peak always greeted the outlook's eye, and

served as a beacon to ships that had as yet no compass to guide

them. Again, the movements of wind and water conspired to help the

sailor reach his goal. A strong central current flowed from the

Black Sea into the Aegean, and countercurrents flowed northward

along the coasts; while the northeasterly etesian winds blew regularly

in the summer to help back to their southern ports the ships that

had gone to fetch grain, fish, and furs from the Euxine Sea. ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Sea )

[ English writers of the 18th century often used Euxine Sea (/ˈjuːksɪn/ or /ˈjuːkˌsaɪn/).[31] During the Ottoman Empire, it was called either Bahr-e Siyah or Karadeniz, both meaning "Black Sea" in Turkish.[32] ]

*02001  < note TURKEY

< note TURKEY

Fog was rare in the Mediterranean, and the unfailing sunshine so

varied the coastal winds that at almost any harbor, from spring to

autumn, one might be carried out by a morning, and brought back by

an evening, breeze.

In these propitious waters the acquisitive Phoenicians and the

amphibious Greeks developed the art and science of navigation. Here

they built ships for the most part larger or faster, and yet more

easily handled, than any that had yet sailed the Mediterranean.

Slowly, despite pirates and harassing uncertainties, the water

routes from Europe and Africa into Asia- through Cyprus, Sidon, and

Tyre, or through the Aegean and the Black Sea- became cheaper than the

long land routes, arduous and perilous, that had carried so much of

the commerce of Egypt and the Near East. Trade took new lines,

multiplied new populations, and created new wealth. Egypt, then

Mesopotamia, then Persia withered; Phoenicia deposited an empire of cities along the African coast, in Sicily, and in Spain; and Greece

blossomed like a watered rose.

"There is a land called Crete, in the midst of the wine-dark sea, a fair, rich land, begirt with water; and therein are many men past counting, and ninety cities."

[ http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0136%3Abook%3D19%3Acard%3D148#:~:text=There%20is%20a%20land%20called,past%20counting%2C%20and%20ninety%20cities.&text=There%20dwell%20Achaeans%2C%20there%20great,waving%20plumes%2C%20and%20goodly%20Pelasgians. ]

'02014 When Homer sang these lines,

perhaps in the ninth century before our era, *02002 Greece had

almost forgotten, though the poet had not, that the island whose

wealth seemed to him even then so great had once been wealthier still;

that it had held sway with a powerful fleet over most of the Aegean

and part of mainland Greece; and that it had developed, a thousand years before the siege of Troy, one of the most artistic civilizations

in history. Probably it was this Aegean culture- as ancient to him

as he is to us- that Homer recalled when he spoke of a Golden Age in

which men had been more civilized, and life more refined, than in

his own disordered time.

The rediscovery of that lost civilization is one of the major

achievements of modern archeology.

Here was an island twenty times

larger than the largest of the Cyclades, pleasant in climate, varied

in the products of its fields and once richly wooded hills, and

strategically placed, for trade or war, midway between Phoenicia and

Italy, between Egypt and Greece. Aristotle had pointed out how

excellent this situation was, and how "it had enabled Minos to acquire

the empire of the Aegean." '02015 But the story of Minos, accepted

as fact by all classical writers, was rejected as legend by modern

scholars; and until sixty years ago it was the custom to suppose, with

Grote, that the history of civilization in the Aegean had begun with

the Dorian invasion, or the Olympic games. Then in A.D. 1878 a

Cretan merchant, appropriately named Minos Kalokairinos, unearthed

some strange antiquities on a hillside south of Candia. *02003 The

great Schliemann, who had but lately resurrected Mycenae and Troy,

visited the site in 1886, announced his conviction that it covered the

remains of the ancient Cnossus, and opened negotiations with the owner

of the land so that excavations might begin at once. But the owner

haggled and tried to cheat; and Schliemann, who had been a merchant

before becoming an archeologist, withdrew in anger, losing a golden

chance to add another civilization to history. A few years later he

died. 02016

In 1893 a British archeologist, Dr. Arthur Evans, bought in Athens a

number of milkstones from Greek women who had worn them as amulets. He

was curious about the hieroglyphics engraved upon them, which no

scholar could read. Tracing the stones to Crete, he secured passage

thither, and wandered about the island picking up examples of what

he believed to be ancient Cretan writing. In 1895 he purchased a part,

and in 1900 the remainder, of the site that Schliemann and the

French School at Athens had identified with Cnossus; and in nine weeks

of that spring, digging feverishly with one hundred and fifty men,

he exhumed the richest treasure of modern historical research- the

palace of Minos. Nothing yet known from antiquity could equal the

vastness of this complicated structure, to an appearances identical

with the almost endless Labyrinth so famous in old Greek tales of

Minos, Daedalus, Theseus, Ariadne, and the Minotaur. In these and

other ruins, as if to confirm Evans' intuition, thousands of seals and

clay tablets were found, bearing characters like those that had set

him upon the trail. The fires that had destroyed the palaces of

Cnossus had preserved these tablets, whose undeciphered pictographs

and scripts still conceal the early story of the Aegean. *02004

Students from many countries now hurried to Crete. While Evans was

working at Cnossus, a group of resolute Italians- Halbherr, Pernier,

Savignoni, Paribeni- unearthed at Hagia Triada (Holy Trinity) a

sarcophagus painted with illuminating scenes from Cretan life, and

uncovered at Phaestus a palace only less extensive than that of the

Cnossus kings. Meanwhile two Americans, Seager and Mrs. Hawes, made

discoveries at Vasiliki, Mochlos, and Gournia; the British- Hogarth,

Bosanquet, Dawkins, Myres- explored Palaikastro, Psychro, and Zakro;

the Cretans themselves became interested, and Xanthoudidis and

Hatzidakis dug up ancient residences, grottoes, and tombs at

Arkalochori, Tylissus, Koumasa, and Chamaizi. Half the nations of

Europe united under the flag of science in the very generation in

which their statesmen were preparing for war.

How was all this material to be classified- these palaces,

paintings, statues, seals, vases, metals, tablets, and reliefs?- to

what period of the past were they to be assigned? Precariously, but

with increasing corroboration as research went on and knowledge

grew, Evans dated the relics according to the depth of their strata,

the gradation of styles in the pottery, and the agreement of Cretan

finds, in form or motive, with like objects exhumed in lands or

deposits whose chronology was approximately known. Digging down

patiently beneath Cnossus, he found himself stopped, some

forty-three feet below the surface, by the virgin rock. The lower half

of the excavated area was occupied by remains characteristic of the

Neolithic Age- primitive forms of handmade pottery with simple

linear ornament, spindle whorls for spinning and weaving,

fat-buttocked goddesses of painted steatite or clay, tools and weapons

of polished stone, but nothing in copper or bronze. *02005

Classifying the pottery, and correlating the remains with those of

ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt, Evans divided the post-neolithic and

prehistoric culture of Crete into three ages- Early, Middle, and

Late Minoan- and each of these into three periods. *02006

The first or lowest appearance of copper in the strata represents

for us, through a kind of archeological shorthand, the slow rise of

a new civilization out of the neolithic stage. By the end of the Early

Minoan Age the Cretans learn to mix copper with tin, and the Bronze

Age begins. In Middle Minoan I the earliest palaces occur: the princes

of Cnossus, Phaestus, and Mallia build for themselves luxurious

dwellings with countless rooms, spacious storehouses, specialized

workshops, altars and temples, and great drainage conduits that

startle the arrogant Occidental eye. Pottery takes on a many-colored

brilliance, walls are enlivened with charming frescoes, and a form

of linear script evolves out of the hieroglyphics of the preceding

age. Then, at the close of Middle Minoan II, some strange

catastrophe writes its cynical record into the strata; the palace of

Cnossus is laid low as if by a convulsion of the earth, or perhaps

by an attack from Phaestus, whose palace for a time is spared. But a

little later a like destruction falls upon Phaestus, Mochlos, Gournia,

Palaikastro, and many other cities in the island; the pottery is

covered with ashes, the great jars in the storerooms are filled with

debris. Middle Minoan III is a period of comparative stagnation, in

which, perhaps, the southeastern Mediterranean world is long

disordered by the Hyksos conquest of Egypt. '02019

In the late Minoan Age everything begins again. Humanity, patient

under every cataclysm, renews its hope, takes courage, and builds once

more. New and liner palaces rise at Cnossus, Phaestus, Tylissus, Hagia

Triada, and Gournia. The lordly spread, the five-storied height, the

luxurious decoration of these princely residences suggest such

wealth as Greece would not know till Pericles. Theaters are erected in

the palace courts, and gladiatorial spectacles of men and women in

deadly combat with animals amuse gentlemen and ladies whose

aristocratic faces, quietly alert, still live for us on the bright

frescoes of the resurrected walls. Wants are multiplied, tastes are

refined, literature flourishes; a thousand industries graciously

permit the poor to prosper by supplying comforts and delicacies to the

rich. The halls of the king are noisy with scribes taking

inventories of goods distributed or received; with artists making

statuary, paintings, pottery, or reliefs; with high officials

conducting conferences, hearing judicial appeals, or dispatching

papers stamped with their finely wrought seals; while wasp-waisted

princes and jeweled duchesses, alluringly decollete, crowd to a

royal feast served on tables shining with bronze and gold. The

sixteenth and fifteenth centuries before our era are the zenith of

Aegean civilization, the classic and golden age of Crete.

III. THE RECONSTRUCTION OF A CIVILIZATION

If now we try to restore this buried culture from the relics that

remain- playing Cuvier to the scattered bones of Crete- let us

remember that we are engaging upon a hazardous kind of historical

television, in which imagination must supply the living continuity

in the gaps of static and fragmentary material artificially moving but

long since dead. Crete will remain inwardly unknown until its secretive tablets find their Champollion.

1. Men and Women

As we see them self-pictured in their art, the Cretans curiously

resemble the double ax so prominent in their religious symbolism. Male

and female alike have torsos narrowing pathologically to an

ultramodern waist. Nearly all are short in stature, slight and

supple of build, graceful in movement, athletically trim. Their skin

is white at birth. The ladies, who court the shade, have fair

complexions conventionally pale; but the men, pursuing wealth under

the sun, are so tanned and ruddy that the Greeks will call them (as

well as the Phoenicians) Phoinikes - the Purple Ones, Redskins. The

head is rather long than broad, the features are sharp and refined,

the hair and eyes are brilliantly dark, as in the Italians of today;

these Cretans are apparently a branch of the "Mediterranean

race." *02007 The men as well as the women wear their hair partly in

coils on the head or the neck, partly in ringlets on the brow,

partly in tresses falling upon the shoulders or the breast. The

women add ribbons for their curls, while the men, to keep their

faces clean, provide themselves with a variety of razors, even in

the grave. '020110

The dress is as strange as the figures. On their heads- most often

bare- the men have turbans or tam-o'-shanters, the women magnificent

hats of our early twentieth-century style. The feet are usually free

of covering; but the upper classes may bind them in white leather

shoes, which among women may be daintily embroidered at the edges,

with colored beads on the straps. Ordinarily the male has no

clothing above the waist; there he wears a short skirt or

waistcloth, occasionally with a codpiece for modesty. The skirt may be

slit at the side in workingmen; in dignitaries and ceremonies it

reaches in both sexes to the ground. Occasionally the men wear

drawers, and in winter a long outer garment of wool or skins. The

clothing is tightly laced about the middle, for men as well as women

are resolved to be- or seem- triangularly slim. '020111 To rival the

men at this point, the women of the later periods resort to stiff

corsets, which gather their skirts snugly around their hips, and

lift their bare breasts to the sun. It is a pretty custom among the

Cretans that the female bosom should be uncovered, or revealed by a

diaphanous chemise; '020112 no one seems to take offense. The bodice

is laced below the bust, opens in a careless circle, and then, in a

gesture of charming reserve, may close in a Medici collar at the neck.

The sleeves are short, sometimes puffed. The skirt, adorned with

flounces and gay tints, widens out spaciously from the hips, stiffened

presumably with metal ribs or horizontal hoops. There are in the

arrangement and design of Cretan feminine dress a warm harmony of

colors, a grace of line, a delicacy of taste, that suggest a rich

and luxurious civilization, already old in arts and wiles. In these

matters the Cretans had no influence upon the Greeks; only in modern

capitals have their styles triumphed. Even staid archeologists have

given the name La Parisienne to the portrait of a Cretan lady with

profulgent bosom, shapely neck, sensual mouth, impudent nose, and a

persuasive, provocative charm; she sits saucily before us today as

part of a frieze in which high personages gaze upon some spectacle

that we shall never see. '020113

The men of Crete are evidently grateful for the grace and

adventure that women give to life, for they provide them with costly

means of enhancing their loveliness. The remains are rich in jewelry

of many kinds: hairpins of copper and gold, stickpins adorned with

golden animals or flowers, or heads of crystal or quartz; rings or

spirals of filigree gold mingling with the hair, fillets or diadems of

precious metal binding it; rings and pendants hanging from the ear,

plaques and beads and chains on the breast, bands and bracelets on the

arm, finger rings of silver, steatite, agate, carnelian, amethyst,

or gold. The men keep some of the jewelry for themselves: if they

are poor they carry necklaces and bracelets of common stones; if

they can afford it they flaunt great rings engraved with scenes of

battle or the chase. The famous Cupbearer wears on the biceps of his

left arm a broad band of precious metal, and on the wrist a bangle

inlaid with agate. Everywhere in Cretan life man expresses his vainest

and noblest passion- the zeal to beautify.

This use of man to signify all humanity reveals the prejudice of a

patriarchal age, and hardly suits the almost matriarchal life of

ancient Crete. For the Minoan woman does not put up with any

Oriental seclusion, any purdah or harem; there is no sign of her being

limited to certain quarters of the house, or to the home. She works

there, doubtless, as some women do even today; she weaves clothing and

baskets, grinds grain, and bakes bread. But also she labors with men

in the fields and the potteries, she mingles freely with them in the

crowds, she takes the front seat at the theater and the games, she

sweeps through Cretan society with the air of a great lady bored

with adoration; and when her nation creates its gods it is more

often in her likeness than in man's. Sober students, secretly and

forgivably enamored of the mother image in their hearts, bow down

before her relics, and marvel at her domination. '020114

2. Society

Hypothetically we picture Crete as at first an island divided by its

mountains among petty jealous clans which live in independent villages

under their own chiefs, and light, after the manner of men,

innumerable territorial wars. Then a resolute leader appears who

unites several clans into a kingdom, and builds his fortress palace at

Cnossus, Phaestus, Tylissus, or some other town. The wars become

less frequent, more widespread, and more efficient in killing; at last

the cities light for the entire island, and Cnossus wins. The victor

organizes a navy, dominates the Aegean, suppresses piracy, exacts

tribute, builds palaces, and patronizes the arts, like an early

Pericles. '020119 It is as difficult to begin a civilization without

robbery as it is to maintain it without slaves. *02008

The power of the king, as echoed in the ruins, is based upon

force, religion, and law. To make obedience easier he suborns the gods

to his use: his priests explain to the people that he is descended

from Velchanos, and has received from this deity the laws that he

decrees; and every nine years, if he is competent or generous, they

reanoint him with the divine authority. To symbolize his power the

monarch, anticipating Rome and France, adopts the (double) ax and

the fleur-de-lis. To administer the state he employs (as the litter of

tablets suggests) a staff of ministers, bureaucrats, and scribes. He

taxes in kind, and stores in giant jars his revenues of grain, oil,

and wine; and out of this treasury, in kind, he pays his men. From his

throne in the palace, or his judgment seat in the royal villa, he

settles in person such litigation as has run the gauntlet of his

appointed courts; and so great is his reputation as a magistrate

that when he dies he becomes in Hades, Homer assures us, the

inescapable judge of the dead. '020121 We call him Minos, but we do

not know his name; probably the word is a title, like Pharaoh or

Caesar, and covers a multitude of kings.

At its height this civilization is surprisingly urban. The Iliad

speaks of Crete's "ninety cities," and the Greeks who conquer them are

astonished at their teeming populations; even today the student stands

in awe before the ruined mazes of paved and guttered streets,

intersecting lanes, and countless shops or houses crowding about

some center of trade or government in all the huddled gregariousness

of timid and talkative men. It is not only Cnossus that is great, with

palaces so vast that imagination perhaps exaggerates the town that

must have been the chief source and beneficiary of their wealth.

Across the island, on the southern shore, is Phaestus, from whose

harbor, Homer tells us, "the dark-prowed ships are borne to Egypt by

the force of the wind and the wave." '020122 The southbound trade of

Minoan Crete pours out here, swelled by goods from northern

merchants who ship their cargoes overland to avoid a long detour by

perilous seas. Phaestus becomes a Cretan Piraeus, in love with

commerce rather than with art. And yet the palace of its prince is a

majestic edifice, reached by a flight of steps forty-five feet wide;

its halls and courts compare with those at Cnossus; its central

court is a paved quadrangle of ten thousand square feet; its

megaron, or reception room, is three thousand square feet in area,

larger even than the great Hall of the Double Ax in the northern

capital.

Two miles northwest is Hagia Triada, in whose "royal villa" (as

archeological imagination calls it) the Prince of Phaestus seeks

refuge from the summer heat. The eastern end of the island, in

Minoan days, is rich in small towns: ports like Zakro or Mochlos,

villages like Praesus or Pseira, residential quarters like

Palaikastro, manufacturing centers like Gournia. The main street in

Palaikastro is well paved, well drained, and lined with spacious

homes; one of these has twenty-three rooms on the surviving floor.

Gournia boasts of avenues paved with gypsum, of homes built with

mortarless stone, of a blacksmith's shop with extant forge, of a

carpenter shop with a kit of tools, of small factories noisy with

metalworking, shoemaking, vasemaking, oil refining, or textile

industry; the modern workmen who excavate it, and gather up its

tripods, jars, pottery, ovens, lamps, knives, mortars, polishers,

hooks, pins, daggers, and swords, marvel at its varied products and

equipment, and call it he mechanike polis - "the town of

machinery." '020123 By our standards the minor streets are narrow,

mere alleys in the style of a semitropical Orient that fears the

sun; and the rectangular houses, of wood or brick or stone, are for

the most part confined to a single floor. Yet some Middle Minoan

plaques exhumed at Cnossus show us homes of two, three, even five

stories, with a cubicle attic or turret here and there; on the upper

floors, in these pictured houses, are windows with red panes of

unknown material. Double doors, swinging on posts apparently of

cypress wood, open from the ground-floor rooms upon a shaded court.

Stairways lead to the upper floors and the roof, where the Cretan

sleeps when the nights are very warm. If he spends the evening indoors

he lights his room by burning oil, according to his income, in lamps

of clay, steatite, gypsum, marble, or bronze. '020124

We know a trifle or two about the games he plays. At home he likes a

form of chess, for he has bequeathed to us, in the ruins of the

Cnossus palace, a magnificent gaming board with frame of ivory,

squares of silver and gold, and a border of seventy-two daisies in

precious metal and stone. In the fields he takes with zest and

audacity to the chase, guided by half-wild cats and slender

thoroughbred hounds. In the towns he patronizes pugilists, and on

his vases and reliefs he represents for us a variety of contests, in

which lightweights spar with bare hands and kicking feet,

middleweights with plumed helmets batter each other manfully, and

heavyweights, coddled with helmets, cheekpieces, and long padded

gloves, fight till one falls exhausted to the ground and the other

stands above him in the conscious grandeur of victory. '020125

But the Cretan's greatest thrill comes when he wins his way into the

crowd that fills the amphitheater on a holiday to see men and women

face death against huge charging bulls. Time and again he pictures the

stages of this lusty sport: the daring hunter capturing the bull by

jumping astride its neck as it laps up water from a pool; the

professional tamer twisting the animal's head until it learns some

measure of tolerance for the acrobat's annoying tricks; the skilled

performer, slim and agile, meeting the bull in the arena, grasping its

horns, leaping into the air, somersaulting over its back, and landing

feet first on the ground in the arms of a female companion who lends

her grace to the scene. '020126 Even in Minoan Crete this is already

an ancient art; a clay cylinder from Cappadocia, ascribed to 2400

B.C., shows a bull-grappling sport as vigorous and dangerous as in

these frescoes. '020127 For a moment our oversimplifying intellects

catch a glimpse of the contradictory complexity of man as we

perceive that this game of blood-lust and courage, still popular

today, is as old as civilization.

3. Religion

The Cretan may be brutal, but he is certainly religious, with a

thoroughly human mixture of fetishism and superstition, idealism and

reverence. He worships mountains, caves, stones, the number 3, trees

and pillars, sun and moon, goats and snakes, doves and bulls; hardly

anything escapes his theology. He conceives the air as filled with

spirits genial or devilish, and hands down to Greece a sylvan-ethereal

population of dryads, sileni, and nymphs. He does not directly adore

the phallic emblem, but he venerates with awe the generative

vitality of the bull and the snake. '020128 Since his death rate is

high he pays devout homage to fertility, and when he rises to the

notion of a human divinity he pictures a mother goddess with

generous mammae and sublime flanks, with reptiles creeping up around

her arms and breasts, coiled in her hair, or rearing themselves

proudly from her head. He sees in her the basic fact of nature- that

man's greatest enemy, death, is overcome by woman's mysterious

power, reproduction; and he identifies this power with deity. The

mother goddess represents for him the source of all life, in plants

and animals as well as in men; if he surrounds her image with fauna

and flora it is because these exist through her creative fertility,

and therefore serve as her symbols and her emanations. Occasionally

she appears holding in her arms her divine child Velchanos, whom she

has borne in a mountain cave. '020129 Contemplating this ancient

image, we see through it Isis and Homs, Ishtar and Tammuz, Cybele and

Attis, Aphrodite and Adonis, and feel the unity of prehistoric

culture, and the continuity of religious ideas and symbols, in the

Mediterranean world.

The Cretan Zeus, as the Greeks call Velchanos, is subordinate to his

mother in the affections of the Cretans. But he grows in importance.

He becomes the personification of the fertilizing rain, of the

moisture that in this religion, as in the philosophy of Thales,

underlies all things. He dies, and his sepulcher is shown from

generation to generation on Mt. Iouktas, where the majestic profile of

his face can still be seen by the imaginative traveler; he rises

from the grave as a symbol of reviving vegetation, and the Kouretes

priests celebrate with dances and clashing shields his glorious

resurrection. '020130 Sometimes, as a god of fertility, he is

conceived as incarnate in the sacred bull; it is as a bull that he

mates in Cretan myth with Minos' wife Pasiphae, and begets by her

the monstrous Minos-bull, or Minotaur.

To appease these deities the Cretan uses a lavish rite of prayer and

sacrifice, symbol and ceremony, administered usually by women priests,

sometimes by officials of the state. To ward off demons he burns

incense; to arouse a negligent divinity he sounds the conch, plays the

flute or the lyre, and sings, in chorus, hymns of adoration. To

promote the growth of orchards and the fields, he waters trees and

plants in solemn ritual; or his priestesses in nude frenzy shake down

the ripe burden of the trees; or his women in festal procession carry

fruits and flowers as hints and tribute to the goddess, who is borne

in state in a palanquin. He has apparently no temple, but raises

altars in the palace court, in sacred groves or grottoes, and on

mountaintops. He adorns these sanctuaries with tables of libation and

sacrifice, a medley of idols, and "horns of consecration" perhaps

representative of the sacred bull. He is profuse with holy symbols,

which he seems to worship along with the gods whom they signify: first

the shield, presumably as the emblem of his goddess in her warrior

form; then the cross- in both its Greek and its Roman shapes, and as

the swastika- cut upon the forehead of a bull or the thigh of a

goddess, or carved upon seals, or raised in marble in the palace of

the king; above all, the double ax, as an instrument of sacrifice

magically enriched with the virtue of the blood that it sheds, or as a

holy weapon unerringly guided by the god, or even as a sign of Zeus

the Thunderer cleaving the sky with his bolts. '020131

Finally he offers a modest care and worship to his dead. He buries

them in clay coffins or massive jars, for if they are unburied they

may return. To keep them content below the ground he deposits with

them modest portions of food, articles for their toilette, and clay

figurines of women to tend or console them through all eternity.

Sometimes, with the sly economy of an incipient skeptic, he

substitutes clay animals in the grave in place of actual food. If he

buries a king or a noble or a rich trader he surrenders to the

corpse a part of the precious plate or jewelry that it once possessed;

with touching sympathy he buries a set of chess with a good player,

a clay orchestra with a musician, a boat with one who loved the sea.

Periodically he returns to the grave to offer a sustaining sacrifice

of food to the dead. He hopes that in some secret Elysium, or

Islands of the Blest, the just god Rhadamanthus, son of Zeus

Velchanos, will receive the purified soul, and give it the happiness

and the peace that slip so elusively through the fingers in this

earthly quest.

4. Culture

The most troublesome aspect of the Cretan is his language. When,

after the Dorian invasion, he uses the Greek alphabet, it is for a

speech completely alien to what we know as Greek, and more akin in

sound to the Egyptian, Cypriote, Hittite, and Anatolian dialects of

the Near East. In the earliest age he confines himself to

hieroglyphics; about 1800 B.C. he begins to shorten these into a

linear script of some ninety syllabic signs; two centuries later he

contrives another script, whose characters often resemble those of the

Phoenician alphabet; perhaps it is from him, as well as from the

Egyptians and the Semites, that the Phoenicians gather together

those letters they will scatter throughout the Mediterranean to become

the unassuming, omnipresent instrument of Western civilization. Even

the common Cretan composes, and like some privy councilor, leaves on

the walls of Hagia Triada the passing inspirations of his muse. At

Phaestus we find a kind of prehistoric printing: the hieroglyphs of

a great disk unearthed there from Middle Minoan III strata are

impressed upon the clay by stamps, one for each pictograph; but

here, to add to our befuddlement, the characters are apparently not

Cretan but foreign; perhaps the disk is an importation from the

East. 020132

The clay tablets upon which the Cretan writes may some day reveal to

us his accomplishments in science. He has some astronomy, for he is

famed as a navigator, and tradition hands down to Dorian Crete the

ancient Minoan calendar. The Egyptians acknowledge their

indebtedness to him for certain medical prescriptions, and the

Greeks borrow from him, as the words suggest, such aromatic and

medicinal herbs as mint ( mintha), wormwood ( apsinthon ), and an

ideal drug ( daukos ) reputed to cure obesity without disturbing

gluttony. '020133 But we must not mistake our guessing for history.

Though the Cretan's literature is a sealed book to us, we may at

least contemplate the rains of his theaters. At Phaestus, about

2000, he builds ten tiers of stone seats, running some eighty feet

along a wall overlooking a flagged court; at Cnossus he raises,

again in stone, eighteen tiers thirty-three feet long, and, at right

angles to them, six tiers from eighteen to fifty feet in length. These

court theaters, seating four or five hundred persons, are the most

ancient playhouses known to us- older by fifteen hundred years than

the Theater of Dionysus. We do not know what took place on those

stages; frescoes picture audiences viewing a spectacle, but we

cannot tell what it is that they see. Very likely it is some

combination of music and dance. A painting from Cnossus preserves a

group of aristocratic ladies, surrounded by their gallants, watching a

dance by gaily petticoated girls in an olive grove; another represents

a Dancing Woman with flying tresses and extended arms; others show

us rustic folk dances, or the wild dance of priests, priestesses,

and worshipers before an idol or a sacred tree. Homer describes the

"dancing-floor which once, in broad Cnossus, Daedalus made for Ariadne

of the lovely hair; there youths and seductive maidens join hands in

the dance... and a divine bard sets the time to the sound of the

lyre." '020134 The seven-stringed lyre, ascribed by the Greeks to

the inventiveness of Terpander, is represented on a sarcophagus at

Hagia Triada a thousand years before Terpander's birth. There, too, is

the double flute, with two pipes, eight holes, and fourteen notes,

precisely as in classical Greece. Carved on a gem, a woman blows a

trumpet made from an enormous conch, and on a vase we see the

sistrum beating time for the dancers' feet.

The same youthful freshness and lighthearted grace that animate

his dances and his games enliven the Cretan's work in the arts. He has

not left us, aside from his architecture, any accomplishments of

massive grandeur or exalted style; like the Japanese of samurai days

he delights rather in the refinement of the lesser and more intimate

arts, the adornment of objects daily used, the patient perfecting of

little things. As in every aristocratic civilization, he accepts

conventions in the form and subject of his work, avoids extravagant

novelties, and learns to be free even within the limitations of

reserve and taste. He excels in pottery, gem cutting, bezel carving,

and reliefs, for here his microscopic skill finds every stimulus and

opportunity. He is at home in the working of silver and gold, sets all

the precious stones, and makes a rich diversity of jewels. Upon the

seals that he cuts to serve as official signatures, commercial labels,

or business forms, he engraves in delicate detail so much of the

life and scenery of Crete that from them alone we might picture his

civilization. He hammers bronze into basins, ewers, daggers, and

swords ornamented with floral and animal designs, and inlaid with gold

and silver, ivory and rare stones. At Gournia he has left us,

despite the thieves of thirty centuries, a silver cup of finished

artistry; and here and there he has molded for us rhytons, or drinking

horns, rising out of human or animal heads that to this day seem to

hold the breath of life.

As a potter he tries every form, and reaches distinction in nearly

all of them. He makes vases, dishes, cups, chalices, lamps, jars,

animals, and gods. At first, in Early Minoan, he is content to shape

the vessel with his hands along lines bequeathed to him from the

Neolithic Age, to paint it with a glaze of brown or black, and to

trust the fire to mottle the color into haphazard tints. In Middle

Minoan he has learned the use of the wheel, and rises to the height of

his skill. He makes a glaze rivaling the consistency and delicacy of

porcelain; he scatters recklessly black and brown, white and red,

orange and yellow, crimson and vermilion, and mingles them happily

into novel shades; he fines down the clay with such confident

thoroughness that in his most perfect product- the graceful and

brightly colored "eggshell" wares found in the cave of Kamares on

Mt. Ida's slopes- he has dared to thin the walls of the vessel to a

millimeter's thickness, and to pour out upon it all the motifs of

his rich imagination. From 2100 to 1950 is the apogee of the Cretan

potter; he signs his name to his work, and his trade-mark is sought

throughout the Mediterranean. In the Late Minoan Age he brings to full

development the technique of faience, and forms the brilliant paste

into decorative plaques, vases of turquoise blue, polychrome

goddesses, and marine reliefs so realistic that Evans mistook an

enamel crab for a fossil. '020135 Now the artist falls in love with

nature, and delights to represent on his vessels the liveliest

animals, the gaudiest fish, the most delicate flowers, and the most

graceful plants. It is in Late Minoan I that he creates his

surviving masterpieces, the Boxers' Vase and the Harvesters' Vase:

in the one he presents us crudely with every aspect and attitude of

the pugilistic game, adding a zone of scenes from the bull-leaper's

life; in the other he follows with fond fidelity a procession probably

of peasants marching and singing in some harvest festival. Then the

great tradition of Cretan pottery grows weak with age, and the art

declines; reserve and taste are forgotten, decoration overruns the

vase in bizarre irregularity and excess, the courage for slow

conception and patient execution breaks down, and a lazy

carelessness called freedom replaces the finesse and tinish of the

Kamares age. It is a forgivable decay, the unavoidable death of an old

and exhausted art, which will lie in refreshing sleep for a thousand

years, and be reborn in the perfection of the Attic vase.

Sculpture is a minor art in Crete, and except in bas-relief and

the story of Daedalus, seldom graduates from the statuette. Many of

these little figures are stereotyped crudities seemingly produced by

rote; one is a delightful snapshot in ivory of an athlete plunging

through the air; another is a handsome head that has lost its body

on the way down the centuries. The best of them excels in anatomical

precision and in vividness of action anything that we know from Greece

before Myron's time. The strangest is the Snake Goddess of the

Boston Museum- a sturdy figure of ivory and gold, half mammae and half

snakes; here at last the Cretan artist treats the human form with some

amplitude and success. But when he essays a larger scale he falls back

for the most part upon animals, and coniines himself to painted

reliefs, as in the bull's head in the Heracleum Museum; in this

startling relic the fixed wild eyes, the snorting nostrils, the

gasping mouth, and the trembling tongue achieve a power that Greece

itself will never surpass.

Nothing else in ancient Crete is quite so attractive as its

painting. The sculpture is negligible, the pottery is fragmentary, the

architecture is in ruins; but this frailest of all the arts, easy

victim of indifferent time, has left us legible and admirable

masterpieces from an age so old that it slipped quite out of the

memory of that classic Greece of whose painting, by contrast so

recent, not one original remains. In Crete the earthquakes or the wars

that overturned the palaces preserved here and there a frescoed

wall; and wandering by them we molt forty centuries and meet the men

who decorated the rooms of the Minoan kings. As far back as 2500

they make wall coatings of pure lime, and conceive the idea of

painting in fresco upon the wet surface, wielding the brush so rapidly

that the colors sink into the stucco before the surface dries. Into

the dark halls of the palaces they bring the bright beauty of the open

fields; they make plaster sprout lilies, tulips, narcissi, and sweet

marjoram; no one viewing these scenes could ever again suppose that

nature was discovered by Rousseau. In the museum at Heracleum the

Saffron Picker is as eager to pluck the crocus as when his creator

painted him in Middle Minoan days; his waist is absurdly thin, his

body seems much too long for his legs; and yet his head is perfect,

the colors are soft and warm, the flowers still fresh after four

thousand years. At Hagia Triada the painter brightens a sarcophagus

with spiral scrolls and queer, almost Nubian figures engrossed in some

religious ritual; better yet, he adorns a wall with waving foliage,

and then places in the midst of it, darkly but vividly, a stout, tense

cat preparing to spring unseen upon a proud bird preening its

plumage in the sun. In Late Minoan the Cretan painter is at the top of

his stride; every wall tempts him, every plutocrat calls him; he

decorates not merely the royal residences but the homes of nobles

and burghers with all the lavishness of Pompeii. Soon, however,

success and a surfeit of commissions spoil him; he is too anxious to

be finished to quite touch perfection; he scatters quantity about him,

repeats his flowers monotonously, paints his men impossibly,

contents himself with sketching outlines, and falls into the lassitude

of an art that knows that it has passed its zenith and must die. But

never before, except perhaps in Egypt, has painting looked so

freshly at the face of nature.

All the arts come together to build the Cretan palaces. Political

power, commercial mastery, wealth and luxury, accumulated refinement

and taste commandeer the architect, the builder, the artisan, the

sculptor, the potter, the metalworker, the woodworker, and the painter

to fuse their s ki lls in producing an assemblage of royal chambers,

administrative offices, court theaters, and arenas, to serve as the

center and summit of Cretan life. They build in the twenty-first

century, and the twentieth sees their work destroyed; they build again

in the seventeenth, not only the palace of Minos but many other

splendid edifices at Cnossus, and in half a hundred other cities in

the thriving island. It is one of the great ages in architectural

history.

The creators of the Cnossus palace are limited in both materials and

men. Crete is poor in metal and quite devoid of marble; therefore they

build with limestone and gypsum, and use wood for entablatures, roofs,

and all columns above the basement floor. They cut the stone blocks so

sharply that they can put them together without mortar. Around a

central court of twenty thousand square feet they raise to three or

four stories, with spacious stairways of stone, a rambling maze of

rooms- guardhouses, workshops, wine press, storerooms,

administrative offices, servants' quarters, anterooms, reception

rooms, bedrooms, bathrooms, chapel, dungeon, throne room, and a

"Hall of the Double Ax"; adding near by the conveniences of a theater,

a royal villa, and a cemetery. On the lowest floor they plant

massive square pillars of stone; on the upper floors they use circular

columns of cypress, tapering strangely downward, to support the

ceilings upon smooth round capitals, or to form shady porticoes at the

side. Safe in the interior against a gracefully decorated wall they

set a stone seat, simply but skillfully carved, which eager diggers

will call the throne of Minos, and on which every tourist will

modestly seat himself and be for a moment some inches a king. This

sprawling palace in all likelihood is the famous Labyrinth, or

sanctuary of the Double Ax (labrys), attributed by the ancients to

Daedalus, and destined to give its name in aftertime to any maze- of

rooms, or words, or ears. *02009 '020136

As if to please the modern spirit, more interested in plumbing

than in poetry, the builders of Cnossus install in the palace a system

of drainage superior to anything else of its kind in antiquity. They

collect in stone conduits the water that flows down from the hills

or falls from the sky, direct it through shafts to the

bathrooms *02010 and latrines, and lead off the waste in terra-cotta

pipes of the latest style- each section six inches in diameter and

thirty inches long, equipped with a trap to catch the sediment,

tapering at one end to lit into the next section, and bound to this

firmly with a necking of cement. '020138 Possibly they include an

apparatus for supplying running hot water to the household of the

king. *02011 020139

To the complex interiors the artists of Cnossus add the most

delicate decorations. Some of the rooms they adorn with vases and

statuettes, some with paintings or reliefs, some with huge stone

amphorae or massive urns, some with objects in ivory, faience or

bronze. Around one wall they run a limestone frieze with pretty

triglyphs and half rosettes; around another a panel of spirals and

frets on a surface painted to simulate marble; around another they

carve in high relief and living detail the contests of man and bull.

Through the halls and chambers the Minoan painter spreads all the

glories of his cheerful art: here, caught chattering in a drawing

room, are Ladies in Blue, with classic features, shapely arms, and

cozy breasts; here are fields of lotus, or lilies, or olive spray;

here are Ladies at the Opera, and dolphins swimming motionlessly in

the sea. Here, above all, is the lordly Cupbearer, erect and strong,

carrying some precious ointment in a slim blue vase; his face is

chiseled by breeding as well as by art; his hair descends in a thick

braid upon his brown shoulders; his ears, his neck, his arm, and his

waist sparkle with jewelry, and his costly robe is embroidered with

a graceful quatrefoil design; obviously he is no slave, but some

aristocratic youth proudly privileged to serve the king. Only a

civilization long familiar with order and wealth, leisure and taste,

could demand or create such luxury and such ornament.

IV. THE FALL OF CNOSSUS

When in retrospect we seek the origin of this brilliant culture,

we find ourselves vacillating between Asia and Egypt. On the one hand,

the Cretans seem kin in language, race, and religion to the

Indo-European peoples of Asia Minor; there, too, clay tablets were

used for writing, and the shekel was the standard of measurement;

there, in Caria, was the cult of Zeus Labrandeus, i.e., Zeus of the

Double Ax (labrys); there men worshiped the pillar, the bull, and

the dove; there, in Phrygia, was the great Cybele, so much like the

mother goddess of Crete that the Greeks called the latter Rhea Cybele,

and considered the two divinities one. '020140a And yet the signs of

Egyptian influence in Crete abound in every age. The two cultures

are at first so much alike that some scholars presume a wave of

Egyptian emigration to Crete in the troubled days of Menes. '020141

The stone vases of Mochlos and the copper weapons of Early Minoan I

are strikingly like those found in Proto-Dynastic tombs; the double ax

appears as an amulet in Egypt, and even a "Priest of the Double Ax";

the weights and measures, though Asiatic in value, are Egyptian in

form; the methods used in the glyptic arts, in faience, and in

painting are so similar in the two lands that Spengler reduced

Cretan civilization to a mere branch of the Egyptian. '020142

We shall not follow him, for it will not do, in our search for the

continuity of civilization, to surrender the individuality of the

parts. The Cretan quality is distinct; no other people in antiquity

has quite this flavor of minute refinement, this concentrated elegance

in life and art. Let us believe that in its racial origins the Cretan

culture was Asiatic, in many of its arts Egyptian; in essence and

total it remained unique. Perhaps it belonged to a complex of

civilization common to all the Eastern Mediterranean, in which each

nation inherited kindred arts, beliefs, and ways from a widespread

neolithic culture parent to them all. From that common civilization

Crete borrowed in her youth, to it she contributed in her maturity.

Her rule forged an order in the isles, and her merchants found entry

at every port. Then her wares and her arts pervaded the Cyclades,

overran Cyprus, reached to Caria and Palestine, '020143 moved north

through Asia Minor and its islands to Troy, reached west through Italy

and Sicily to Spain, '020144 penetrated the mainland of Greece even

to Thessaly, and passed through Mycenae and Tiryns into the heritage

of Greece. In the history of civilization Crete was the first link in

the European chain.

We do not know which of the many roads to decay Crete chose; perhaps

she took them all. Her once famous forests of cypress and cedar

vanished; today two thirds of the island are a stony waste,

incapable of holding the winter rains. '020145 Perhaps there too, as

in most declining cultures, population control went too far, and

reproduction was left to the failures. Perhaps, as wealth and luxury

increased, the pursuit of physical pleasure sapped the vitality of the

race, and weakened its will to live or to defend itself; a nation is

born stoic and dies epicurean. Possibly the collapse of Egypt after

the death of Ikhnaton disrupted Creto-Egyptian trade, and diminished

the riches of the Minoan kings. Crete had no great internal resources;

her prosperity required commerce, and markets for her industries; like

modern England she had become dangerously dependent upon control of

the seas. Perhaps internal wars decimated the island's manhood, and

left it disunited against foreign attack. Perhaps an earthquake

shook the palaces into ruins, or some angry revolution avenged in a

year of terror the accumulated oppressions of centuries.

About 1450 the palace of Phaestus was again destroyed, that of Hagia

Triada was burned down, the homes of the rich burghers of Tylissus

disappeared. During the next fifty years Cnossus seems to have enjoyed

the zenith of her fortune, and a supremacy unquestioned throughout the

Aegean. Then, about 1400, the palace of Cnossus itself went up in

flames. Everywhere in the ruins Evans found signs of uncontrollable

fire-charred beams and pillars, blackened walls, and clay tablets

hardened against time's tooth by the conflagration's heat. So thorough

was the destruction, and so complete the removal of metal even from

rooms covered and protected by debris, that many students suspect

invasion and conquest rather than earthquake. *02012 '020146 In

any case, the catastrophe was sudden; the workshops of artists and

artisans give every indication of having been in full activity when

death arrived. About the same time Gournia, Pseira, Zakro, and

Palaikastro were leveled to the ground.

We must not suppose that Cretan civilization vanished overnight.

Palaces were built again, but more modestly, and for a generation or

two the products of Crete continued to dominate Aegean art. About

the middle of the thirteenth century we come at last upon a specific

Cretan personality- that King Minos of whom Greek tradition told so

many frightening tales. His brides were annoyed at the abundance of

serpents and scorpions in his seed; but by some secret device his wife

Pasiphae eluded these, '020147 and safely bore him many children,

among them Phaedra (wife of Theseus and lover of Hippolytus) and the

fair-haired Ariadne. Minos having offended Poseidon, the god afflicted

Pasiphae with a mad passion for a divine bull. Daedalus pitied her,

and through his contrivance she conceived the terrible Minotaur. Minos

imprisoned the animal in the Labyrinth which Daedalus had built at his

command, but appeased it periodically with human sacrifice. '020148

Pleasanter even in its tragedy is the legend of Daedalus, for it

opens one of the proudest epics of human history. Greek story

represented him as an Athenian Leonardo who, envious of his nephew's

skill, slew him in a moment of temperament, and was banished forever

from Greece. He found refuge at Minos' court, astonished him with

mechanical inventions and novelties, and became chief artist and

engineer to the king. He was a great sculptor, and fable used his name

to personify the graduation of statuary from stiff, dead figures to

vivid portraits of possible men; the creatures made by him, we are

informed, were so lifelike that they stood up and walked away unless

they were chained to their pedestals. '020149 But Minos was peeved

when he learned of Daedalus' connivance with Pasiphae's amours, and

confined him and his son Icarus in the maze of the Labyrinth. Daedalus

fashioned wings for himself and Icarus, and by their aid they leaped

across the walls and soared over the Mediterranean. Disdaining his

father's counsel, proud Icarus flew too closely to the sun; the hot

rays melted the wax on his wings, and he was lost in the sea, pointing

a moral and adorning a tale. Daedalus, empty-hearted, flew on to

Sicily, and stirred that island to civilization by bringing to it

the industrial and artistic culture of Crete. *02013 '020150

More tragic still is the story of Theseus and Ariadne. Minos,

victorious in a war against youthful Athens, exacted from that city,

every ninth year, a tribute of seven girls and seven young men, to

be devoured by the Minotaur. On the coming of the third occasion for

this national humiliation the handsome Theseus- his father King Aegeus

reluctantly consenting- had himself chosen as one of the seven youths,

for he was resolved to slay the Minotaur and end the recurrent

sacrifice. Ariadne pitied the princely Athenian, loved him, gave him a

magic sword, and taught him the simple trick of unraveling thread from

his arm as he penetrated the Labyrinth. Theseus killed the Minotaur,

followed the thread back to Ariadne, and took her with him on his

flight from Crete. On the isle of Naxos he married her as he had

promised, but while she slept he and his companions sailed

treacherously away. *02014 '020152

With Ariadne and Minos, Crete disappears from history till the

coming of Lycurgus to the island, presumably in the seventh century.

There are indications that the Achaeans reached it in their long raid

of Greece in the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries, and Dorian

conquerors settled there towards the end of the second millennium

before Christ. Here, said many Cretans and some Greeks, '020153

Lycurgus, and in less degree Solon, had found the model for their

laws. In Crete as in Sparta, after the island had come under Dorian

sway, the ruling class led a life of at least outward simplicity and

restraint; the boys were brought up in the army, and the adult males

ate together in public mess halls; the state was ruled by a senate of

elders, and was administered by ten kosmoi or orderers,

corresponding to the ephors of Sparta and the archons of

Athens. '020154 It is difficult to say whether Crete taught Sparta,

or Sparta Crete; perhaps both states were the parallel results of

similar conditions- the precarious life of an alien military

aristocracy amid a native and hostile population of serfs. The

comparatively enlightened law code of Gortyna, discovered on the walls

of that Cretan town in A.D. 1884, belongs apparently to the early

fifth century; in an earlier form it may have influenced the

legislators of Greece. In the sixth century Thaletas of Crete taught

choral music at Sparta, and the Cretan sculptors Dipoenus and Scyllis

instructed the artists of Argos and Sicyon. By a hundred channels the

old civilization emptied itself out into the new.

CHAPTER II: Before Agamemnon

I. SCHLIEMANN

IN the year 1822 a lad was born in Germany who was to turn the

spadework of archeology into one of the romances of the century. His

father had a passion for ancient history, and brought him up on

Homer's stories of the siege of Troy and Odysseus' wanderings. "With

great grief I heard from him that Troy had been so completely

destroyed that it had disappeared without leaving any trace of its

existence." '02021 At the age of eight, having given the matter

mature consideration, Heinrich Schliemann announced his intention to

devote his life to the rediscovery of the lost city. At the age of ten

he presented to his father a Latin essay on the Trojan War. In 1836 he

left school with an education too advanced for his means, and became a

grocer's apprentice. In 1841 he shipped from Hamburg as cabin boy on a

steamer bound for South America. Twelve days out the vessel foundered;

the crew was tossed about in a small boat for nine hours, and was

thrown by the tide upon the shores of Holland. Heinrich became a

clerk, and earned a hundred and fifty dollars a year; he spent half of